Sarah Senette

“She couldn’t survey the wreck of the world with an

air of casual unconcern”[1]

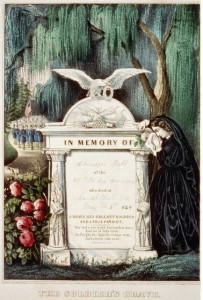

In The Soldier’s Grave, (figure one) a young woman kneels among the somber branches of a willow tree. Dressed in black, the woman clutches the un-inscribed tombstone as she holds a tissue to her downturned face. In the distance indistinct soldiers march into battle, leaving the woman to suffer alone.

Currier and Ives, New York, 1865

Library of Congress (figure one)

The young woman’s prominence in The Soldier’s Grave, especially in comparison to the ghost-like men in the background, signifies fundamental changes in southern society following the American Civil War.[2] The death of so many young men, “transformed the American nation as well as hundreds of thousands of individuals directly affected by loss.”[3] In light of this void, women of all socioeconomic avenues accepted the challenge of rebuilding the South.[4] For example, Confederate women aimed at perpetuating a “memory framework” valorizing the Confederate dead and building upon a shared belief in white supremacy, known as Lost Cause ideology. Monuments glorifying Confederate heroes embodied their vision of the South quite well.[5] African American teachers, meanwhile, had little interest in commemorating the men who helped defend slavery or perpetuating white supremacy. Seeking racial equality, black women used images that demonstrated their adherence to the “politics of respectability” to achieve this purpose.[6] While any study of women during the Civil War and Reconstruction must engage with the range of their roles, the very vast diversity of scholarship of women during that time can somewhat obscure the essential position of women as shapers of the post-war South.[7] As such, this essay examines the ways in which women from a number of different backgrounds sought to reshape the South following the overwhelming death and massive social upheaval of the Civil War, attending to the different concerns and activities of Confederate women, northern reformers, and formerly enslaved women. While each group had different and occasionally conflicting aims, they were all important players in—and shapers of— the post war South.

Confederate Women, Domesticity, and Lost Cause Ideology

“They have adapted themselves . . . with the fortitude that belongs

to every true woman.”[8]

In general, southern women adopted a socially conservative approach, despite expanding their activities into the public sphere. Rebuilding both antebellum social order and the physical environment became the most popular reform of southern women, who took on role of the ‘preservers’ of southern culture. In so doing, they became champions of Lost Cause ideology. While Lost Cause ideology glorified pre-war southern society, it also functioned as “a collective memory,” that emphasized the bravery of the Confederates soldiers who had died for a noble cause— in a war fought in the name of states’ rights— not slavery.[9] For southern women, as cultural standard-bearers, perpetuating Lost Cause ideology also meant commemorating the South and Confederate heroes. Southern women, although largely un-credited, were very frequently the “primary actors” and driving force behind monumental commemorative architecture.[10]

As demonstrated by the upright stance and hand gestures of the women in a photograph of the unveiling ceremony for the Confederate monument at Salisbury, southern women took pride in their ability to perpetuate what they believed to be southern ideals through public monuments (figure two).

1909. North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library (figure two)

Additionally, the Salisbury monument occupies the center of a broad, tree-lined boulevard, indicating its centrality in the physical and social landscape. The statue’s height, the fact that it rests on a dais, and the mounded earth supporting the statue, suggests the desired ideological impact of the monument on the local population. The statue, like the ideas it represents, is ‘above it all’ and embodies the ostensibly high-minded Lost Cause ideology. The ladies stand at the statues’ base, visually underpinning it, the ideology it represents, and their public place in reshaping the southern landscape.[11]

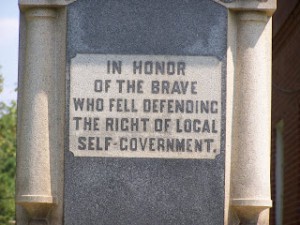

Southern women’s activism in memorial architecture occurred both as a response to severely altered demographics in the South and the need to bury and commemorate Civil War soldiers.[12] Throughout the South, southern women rallied together in local ladies memorial associations for the express purpose of commemorating the valorous dead. In Georgia, for example, the ladies memorial association along with the United Daughters of the Confederacy erected the Greene County Confederate Monument in Greensboro (figure three). Similar in style to much of the commemorative architecture of the period in its raised dais and use of a single elevated soldier, the Greensboro monument unabashedly connects itself to Lost Cause ideology through its engraving on the base, which reads: “in honor of the brave who fell defending the right of local self government.” (figure four) Similarly, the Confederate monument at St Joseph’s Cemetery in Bardstown, Kentucky, (figure five) depicts a single soldier on a raised platform. Erected in 1903 by the J. Crepps Wickliffe Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, its inscription is slightly more circumspect.

The statue reads: “Marble tells not of their valor’s worth . . . Whether unknown, or known to fame, their cause and country still the same, they died and wore the gray.” Here, the women of the Wickliffe Chapter link the grey uniforms of the Confederacy with, ‘valor, cause, country, and same.’ In so doing, they assert that Confederate principles are not at odds with American principles and that all Civil War soldiers died for noble purposes. Moreover, the statue also bears the image of General Robert E. Lee directly underneath the figure of the unnamed soldier. In using the famous likeness of Lee, often thought of as the defender of the South, the women of the Wickliffe Chapter likewise cast themselves as protectors of the memory of the Confederate soldiers and southern heritage more broadly.[13]

After the failure of Reconstruction, ladies’ memorial associations, often in conjunction with the United Daughters of the Confederacy, erected hundred of commemorative statues throughout the South fundamentally reshaping the southern landscape and post war southern identity.[14] Indeed, through public monuments Confederate women became perhaps the most potent force in shaping white southern memories of the Civil War and shaping the collective identity of the post war South. Between the work of both national and local ladies memorial associations, southern women “built monuments in almost every city, town, and state of the former Confederacy.”[15] Southern women achieved so much success in their efforts to shape the post-war South that General Cable, head of the United Confederate Veterans, asserted “’all the good’ that was being accomplished in the South was through ‘women’s work.’”[16] Yet, in their desire to rebuild southern identity around Lost Cause ideology, southern women fundamentally changed their established place in society. Women assumed “semipublic leadership roles heretofore unfamiliar in most of the South.”[17] This new public role radically differed from the pre war ideal of elite white women as belonging solely to the domestic sphere.[18] Ironically, in their ‘preservation’ southern culture and traditional southern society, southern women irreconcilably altered their role in it and laid the basis for a new post-war identity.

Respectability, Education, and Reconstruction

“That they may benefit and elevate their race:”[19]

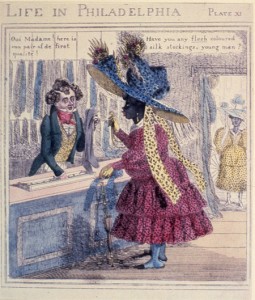

On the other side of the struggle to reshape the post-war South, northern women reformers, both white and black, most often chose missionary or educational avenues of reform as their method of transforming post-war society. Modeled upon white upper-class definitions of social propriety, African American women sought to dispel persistent racial stereotypes that depicted women of color as incapable of embodying nineteenth-century ideals of female virtue. Due to the rigid racial structure in the South in the years before the war, most, though not all, of the women of color who participated in reform activities during Reconstruction came from the North and held a more socially precarious position than their white northern female counterparts.[20] Women reformers of color likewise understood that they must always personally represent proper nineteenth-century social values as an example to whites of African American racial equality and fitness for equal social and political participation. This need to defend their respectability in images also stems from the fact that, prior to the war, images that ridiculed the very notion that African American women could attain respectability abounded (figure six).

For example, E. W. Clay produced a series of cartoons entitled, Life in Philadelphia that mocked Philadelphia’s community of relatively affluent free African Americans. One cartoon, portrays a northern African American woman in garish dress attempting to buy ‘flesh colored’ i.e. white stockings. Her ridiculous garments, apparently useless monocle, and low sloping forehead suggest to the viewer that this woman, despite her wealth, cannot be a lady. The figure’s racialized features, moreover, recall nineteenth-century scientific drawings meant to depict the sub-human characteristics of non-whites. The illustrator also suggests that free women of color in Philadelphia have forgotten their appropriate social place and now see themselves as essentially white.

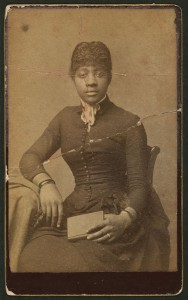

In reaction to such images, photographs of African American women following the Civil War thus often represent them as proper and respectable. Photography represented an ideal medium for post-war propaganda because, due to its indexical connection material reality and ability to be mass produced, many individuals believed photos inherently more truthful than drawings. [21] In Three Quarter Length Portrait of an African American Woman Holding a Book, for example, the subject wears a high collared somber dress (figure seven).

photographic print on carte de visite, between 1870-1890 Edwards’ Excelsior Photo. Gallery, 804 Main Street, Lynchburg Library of Congress, Washington D.C. (figure seven)

She gazes temperately out at the viewer with a direct and intelligent countenance. Beyond her gaze, she informs the viewer of her education by holding a book in her lap. Indeed, her thumb still holds her place as if she has only just looked up from reading and will return to it soon. While an image of one socially respectable woman, Three Quarter Length Portrait demonstrates to society-at-large, and, given its origins in Virginia, likely the South in particular, that African American women could be social equals. The fact that the image appears on a carte de visite, an easily mass-produced medium, denotes its public element. The photo’s Virginia origins are also symbolically significant in this photograph as it was the first of the thirteen American colonies to have enslaved people, the first to make slavery hereditary through the female line, and often considered the birthplace of American politics. Geographically and symbolically, this image would have connected African American slavery, American politics, and African American women’s respectability in the mind of the viewer.[22]

For northern women of color specifically, reform meant racial uplift, “the idea that educated blacks [were] responsible for the welfare of the majority of the race,” a sentiment discernible in the black clubwomen’s motto ‘lifting as we climb.’[23] Northern African Americans reformers’ “bourgeois respectability shaped black female activists’ desire to act as unblemished representatives of the race.”[24] By “embed[ing] bourgeois respectability in racial uplift ideology,” the scope of African American women’s reforms mirrored popular northern white women’s reforms such as “temperance and education.”[25] Thus, as it was for white women, teaching became a calling of northern African American reformers. One of the most well-known African American school teachers, Charlotte Forten Grimke, thought that her students “should know what one of their own color could do for his race.” She “long[ed] to inspire them with courage and ambition.”[26] Grimke, like her counterparts, knew that courage would be a necessary ingredient for future success as she, like her students, faced open hostility from whites.[27]

Although a northerner, Grimke knew of the near ubiquity of racial prejudice against African Americans around the time of the Civil War. Grimke grew up in a middle-class family of Philadelphia abolitionists, who surrounded themselves with a community of respectable African American men and women— precisely the kind lampooned and ultimately denied in the Life in Philadelphia cartoons.[28] While much of Grimke’s life was exceptional, her use of the politics of respectability to promote racial uplift acts as a template for patterns of northern African American women reformers in general. For example, Grimke’s self portrait bears an uncanny resemblance to Three-quarter-length Portrait (figure eight). Both women wear high collared somber dresses, indicating serious intent and lack of sexual promiscuity. Moreover, both women hold open books in their lap, suggesting education and middle-class values. While Grimke undoubtedly possessed these traits, the fact that the woman in Three-quarter-length Portrait replicates them so closely indicates the wide-spread influence of respectability politics in African American women’s reform movements. Women of color, like Grimke, “saw the activist potential of education and skillfully used this ‘female sphere’ of influence to foster a definition of education as the cornerstone of racial uplift.”[29] Thus, strategic self-fashioning, promotion of African women’s respectability, and education shaped the nature of African American women’s reform movements in the years following the Civil War.

Formerly Enslaved Women and the Continuing Struggle for Equality

“Times don’t change, just the merchandise.”[30]

Generally poor, uneducated, and living amidst the physical destruction of the South, formerly enslaved women faced perhaps the most difficulties of any group of women in the years following the Civil War. Initially, northern women reformers, black and white, sought to implement the same model of white respectability in their attempts to uplift formerly enslaved women. Yet, between the underlying racist perspective of many white northern teachers and continuing economic confines, few formerly enslaved women fully attained this white middle-class model of female domesticity. After white women reformers’ “initial feelings of womanly compassion,” collapsed “teachers became frustrated with their uplift efforts.”[31] White teachers often employed formerly enslaved women, rather than teaching them “the virtues of neatness and cleanliness.”[32] Indeed, some white teachers openly sympathized with former plantation mistresses over the difficulty of managing their former slaves.

As Reconstruction wore on, this growing divide between white female domesticity and African American femininity centered on the issue of formerly enslaved women’s work in and outside of the home. While formerly enslaved women received housewifery training, it came with ‘practical’ limitations because of white expectations that they continue to labor in the fields. Not mincing words about the role of formerly enslaved women, U.S. Treasury agent Edward Pierce asserted, “better a woman with a hoe, than without it, when she is not yet fit for the needle or the book” and white teacher generally agreed.[33] When taken in conjunction with the economic hardships that continued in the South over the course of Reconstruction, white teachers’ limited view of formerly enslaved women’s ability to attain respectability worked against the desires of newly free women.

While formerly enslaved women did take advantage of new, albeit abbreviated, opportunities in education and the public sphere, such as the anti-lynching and overtly political campaigns toward the end of Reconstruction, most did not.[34] Most newly freed women’s attempts to reshape southern society began at home. They rarely shared northern white women’s desire for them to work outside their residence. Indeed, “after generations of being denied the opportunity to do so . . . many wanted to stay at home with their families.”[35] Thus, white society frequently charged formerly enslaved women with ‘female loafer-ism’ for attempting to attain the most traditional female role in southern and American society: stay-at-home mother.[36]

In overwhelming numbers following the Civil War, formerly enslaved women legally married their spouses, located their children, and attempted to create conventional, nineteenth-century family units. Newspaper advertisements and letters to the Freedmen’s Bureau in search of missing husbands, children, and extended family, provide some of the most compelling evidence of this desire to rebuild family following the war. Mrs. Charlotte Powell, a formerly enslaved women living in Sacramento, represents one such example when she advertised for “information of her relatives, consisting of her father, mother, three brothers, and two sisters. Her father’s name was Sam Mosley; he was owned by a man named Joe Powell, who lived in Kentucky.”[37] No anomaly, this advertisement represents but one of a multitude of such entreaties from formerly enslaved women in an attempt rebuild their families and create socially recognized family units following the Civil War.[38]

Economic and political pressure, particularly after the failure of Reconstruction, soon forced formerly enslaved women out of their homes and back into the workforce. Images such as Woman Washing Laundry in the Vicinity of Fifteenth Street (figure nine) demonstrates some of hardships that formerly enslaved women faced post war.

http://www.newsouthassoc.com/springfield/history1.html (figure nine)

The unnamed laundress bends over her washboard in full exposed to the elements. Dust rolls by, likely dirtying the painstakingly cleaned sheets. The ramshackle houses and poor clothing, suggests the overall level of poverty that formerly enslaved women endured during Reconstruction. In part, this poverty occurred because aid from the Freedmen’s Bureau often took a long time to secure, if it came at all. Formerly enslaved women, like the unnamed woman in Woman Washing Laundry, often had to continue working in poor conditions in the interim. After the betrayal of formerly enslaved people through the ‘Compromise’ of 1877, and the end of Reconstruction, this dilemma intensified for women. [39] Women, like the one depicted in Interior of a Kitchen at Refuge Plantation Camden County Georgia (figure ten), soon found themselves working for the same people and in the same spaces as they had under slavery.

Photograph by L.D. Andrew, 1936, from a vintage photograph taken ca. 1880

(figure ten)

Nor was domestic labor, post war, physically much better than field work. In Interior of a Kitchen the African American cook poses next to a large sooty fireplace, at which she likely spent most of her day. The sweltering heat, particularly in the summer would have been almost unbearable, not to mention the heavy iron pots and pans. Yet, the unnamed cook gazes directly back at the viewer. Her upright posture suggests that she is not cowed. Regardless of the similarities in her position now to before the Civil War, she embraces one fundamental change: she is free. Historians of slavery and the failure of Reconstruction often debate whether freedom without material change had any practical value as race relations actually became more violent following Reconstruction.[40] Regardless of any lack of change in their material condition, formerly enslaved women gradually challenged white supremacy, and ultimately reshaped southern society, because of their ‘nominal’ freedom. Small victories, such as the right to live separately from where they worked, slowly increased formerly enslaved women’s autonomy. Likewise, their shared trials created a community and infrastructure that some historians see as foundational to African American struggles for equality more broadly.[41] Formerly enslaved women may not have had the immediate impact of any of their female counterparts, but perhaps in the larger narrative they were the most potent catalysts of change.

Conclusion

“The prejudice against color, of which we hear so much,

is no stronger than that against sex.” [42]

Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s statement, which opens this section, is problematic because, although it uses womanhood as a unit of analysis, it erroneously conflates all women’s experiences. All women in post Civil War society endured some measure of disenfranchisement, but it was by no means equal. Women of color, be they former slaves or not, fought against both racial and gender prejudice. This intersectionality of race and gender affected all women in different ways and thus produced different ideas of how to reform society. While sometimes overlapping, women reformers could also be directly at odds with one another. For instance, northern women of color sought to promote racial equality and were directly countered by southern white women’s desire to romanticize pre-war society. Although undoubtedly true, this diversity overlooks the centrality of women’s reform movements in all parts of southern society during Reconstruction.[43] Following the overwhelming death and massive social upheaval of the Civil War, regardless of their different agendas, women became the instruments of reform and the shapers of the post war South.

[1] Margaret Mitchell, Gone with the Wind (New York: Macmillan, 1936), 600.

[2] Mark S. Schantz, Awaiting the Heavenly Country: The Civil War and America’s Culture of Death (New York: Cornell University Press, 2013), 178-180.

[3] Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), xii-xiii.

[4] In exploring their actions, historians of women in the Civil War and Reconstruction have published a vast array of work. Their efforts result in a plethora of diverse scholarship reflecting the diversity of women’s roles during this time. For an overview of the field see: Jeannie Whayne, “Southern Women During the Age of Emancipation” and Nina Silber “Northern Women During the Age Of Emancipation: And then the War Came” in A Companion to the Civil War and Reconstruction ed. Lacy Ford (New York: Blackwell publishers, 2011).

[5] Keith D. Dickson, Sustaining Southern Identity: Douglas Southall Freeman and Memory in the Modern South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011), 219. Top of FormBottom of Form

[6] Jane E. Dabel, A Respectable Woman: The Public Roles of African American Women in 19th-Century New York (New York University Press, 2008), 158; Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920 (Harvard University Press, 1994), 185.

[7] Marilyn Mayer Culpepper, All Things Altered: Women in the Wake of Civil War and Reconstruction (New York, McFarland , 2002), 293-294.

[8] Mary Washington Cable in Victoria E. Ott, Confederate Daughters: Coming of Age During the Civil War (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 163.

[9]Please note that the term has many connotations and can serve many different aspects of post war society. I have selected this relatively simple definition because it includes what I consider the three main features of Lost Cause ideology: valorization of Confederate dead, collective memory, and pre-war nostalgia. Glenn W Lafantasie, Gettysburg Requiem: The Life and Lost Causes of Confederate Colonel William C. Oates (Oxford University press, 2006), xxiii.

[10] Caroline E. Janney, Burying the Dead, But Not the Past: Ladies Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), ix.

[11] Cynthia Mills and Pamela H. Simpson, eds. Monuments to the Lost Cause: Women, Art, and the Landscapes of Southern Memory (University of Tennessee Press, 2003), xv, xvi, xviii.

[12] Faust, This Republic of Suffering, 170, 240, 242-243, 244, 247.

[13] For a discussion about the Lee’s continuing role as the ‘defender’ of southern values see: Rebecca Bridges Watts Contemporary Southern Identity: Community Through Controversy (University of Mississippi Press, 2007) 78-79.

[14] Mills and Simpson, eds. Monuments to the Lost Cause, 220, 221; H. Gulley, “Women and the Lost Cause: Preserving a Confederate Identity in the American Deep South” Journal of Historical Geography 19 no. 2 (April 1992), 125, 126-127, 128, 129, 130.

[15] Karen L. Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2003), 49.

[16] Ibid, 52;Victoria E. Ott, Confederate Daughters: Coming of Age During the Civil War (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 7, 148-157; http://docsouth.unc.edu/highlights/dixon.html (accessed 2/10/15).

[17] Mills and Simpson, eds. Monuments to the Lost Cause, 4.

[18] Lafantasie, Gettysburg Requiem, 212-213.

[19] Mary Church Terrell in Maureen Moynagh and Nancy Forestell, eds. Documenting First Wave Feminisms: Volume 1: Transnational Collaborations and Crosscurrents (University of Toronto Press, 2012), 342.

[20] Heather Andrea Williams, Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 7-9.

[21] Brian Wallis, “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes,” American Art (Summer 1995), 46, 47, 48.

[22] Edmund Morgan, American slavery American Freedom (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 1975), 4, 5-6.

[23] Kevin K. Gaines, “’Racial Uplift Ideology in the Era of “the Negro Problem’” http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1865-1917/essays/racialuplift.htm (accessed 3/7/15)

[24]Victoria W. Wolcott, Remaking Respectability: African American Women in Interwar Detroit (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 6.

[25] Ibid., 7.

[26] Gerda Lerner, ed., Black Women in White America: a Documentary History (Vintage Books, New York, 1972), 96.

[27] Crystal Nicole Feimster, Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching (Harvard University Press, 2009), 114-117.

[28]“Charlotte Forten Grimke (1837-1914)” https://www.nwhm.org/educationresources/biography/biographies/charlotte-forten-grimke/ (accessed 3/7/15)

[29] Karen Johnson, Uplifting the Women and the Race: The Lives, Educational Philosophies and Social Activism of Anna Julia Cooper and Nannie Helen Burroughs (New York: Routaledge, 2000), 160.

[30] Sarah Graves, former slave from Nodaway County, MO. Used as part of the Missouri State Museum’s Slavery’s Echoes exhibit. To see the exhibit and hear her interview visit: http://mostateparks.com/page/58368/slaverys-echoes-interviews-former-missouri-slaves. For the original interview visit he Works Progress Administrations interviews available at: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/snhtml/snhome.html.

[31] Nina Sibler, “A Compound of Wonderful Potency: Women teachers of the North in the Civil War South,” in The War was You and Me: Civilians in the American Civil War, ed., Joan E. Cashin (Princeton University Press, 2002), 51.

[32]Ibid., 52.

[33] Nina Silber, Daughters of the Union: northern women fight the Civil War (Harvard University Press, 2009), 245.

[34] Lisa G. Materson, For the Freedom of Her Race: Black Women and Electoral Politics in Illinois, 1877-1932: Black Women and Electoral Politics in Illinois, 1877-1932 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 3, 4, 8-10, 12, 15, 113.

[35] Elizabeth Regosin Freedom’s Promise: Ex-Slave Families and Citizenship in the Age of Emancipation (University of Virginia Press, 2002), 145.

[36] Shirley Wilson Logan, We are Coming: The Persuasive Discourse of Nineteenth-century Black Women, (Southern Illinois University Press, 1999), 105.

[37] “ Information Wanted Ad” in Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, http://nkaa.uky.edu/record.php?note_id=2612 (accessed 2/12/15)

[38] Heather Andrea Williams, Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), v, vi, viii, x.

[39] Rebecca Sharpless, Cooking in Other Women’s Kitchens: Domestic Workers in the South,1865-1960, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), iv-xii.

[40] The question of the relationship between African American agency and Reconstruction’s failure dates , at least, to W.E.B Dubois 1935 publication, however, for a concise assessment of the state of the field, see John C. Rodrigue’s “Black Agency after Slavery” , 40-65, in Reconstructions: New Perspectives on Postbellum America, edited by Tomas Brown,( Oxford University Press, 2006).

[41]Sharpless, Cooking in Other Women’s Kitchens, xi-xii, xiii, xv, xvii-xviii; Danielle L. McGuire, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, Resistance, A New History of the Civil Rights Movement (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), xix, xx, xxi, xxii.

[42] Elizabeth Cady Stanton in History of Woman Suffrage: 1848-1861, Vol. 1, edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan Brownell Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, Ida Husted Harper (New York: Fowler & Wells, 1889), 681.

[43]Jeannie Whayne, “Southern Women During the Age of Emancipation” in A Companion to the Civil War and Reconstruction ed. Lacy Ford (New York: Blackwell publishers, 2011) for page number see: https://books.google.com/books?id=xeQAERwie80C&pg=RA3-PT351&dq=historiography+of+women+in+civil+war+and+reconstruction&hl=en&sa=X&ei=K-n9VO-OAs22yATCpoDIAQ&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=historiography%20of%20women%20in%20civil%20war%20and%20reconstruction&f=false

Your panoramic view of post-war female reformers provides an interesting and multi-faceted snapshot of the time period. The discussion of collective memory and Lost Cause mentality as it pertained to the construction of Confederate monuments was especially interesting when looked at in conjunction with the discussion of northern women of color’s social reform method of “racial uplift.” These concepts of reform became clear when seen through the manufactured monuments and photos that presented certain ideas about the romanticized identity of the antebellum South and the quest for social redemption and equality, respectively.

Sarah, I really appreciate your effort to present a broad view of women’s roles in shaping the postbellum South. You carefully attend to difference while bringing into relief the increased opportunities for active participation in the public sphere afforded to women of diverse backgrounds after the war. Any one of your sections could have been a paper in and of itself (and a good one!), but bringing them together offers an important perspective as well.