During the Civil War, political cartoonist Thomas Nast vehemently supported the Union and opposed slavery through his illustrations in the critically acclaimed publication, Harper’s Weekly. He gained popularity with its readers through his sentimental illustrations, like Christmas Eve, that featured his unique compositional style (Fig.1). The double-circle method he used captivates the viewer and provides a clear focus. On the left, a woman

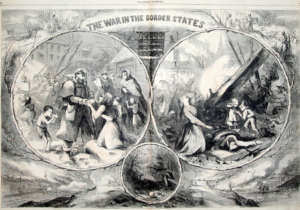

gazes longingly through her window as she prays for the safety of her husband. On the right, a soldier, presumably her husband, sits alone beside a fire. The imagery aims to be both emotional and relatable.[1] The popularity of this image paved the way for Nast to express himself freely and comment on political matters with Harper’s Weekly’s support. Shortly after the popularity of Christmas Eve, the magazine published Nast’s The War in the Border States (Fig. 2). Here, Nast pushes the limits of critiquing the war by revealing the darker side: the misery of women and children.[2] On the left, a Union soldier feeds a starving mother and her children. On the right, Nast displays the anguish of a family who has lost their patriarch. This illustration of

strife further solidified Nast’s popularity and therefore his artistic freedom. He went on to use this freedom to create one of the most controversial images of his career.

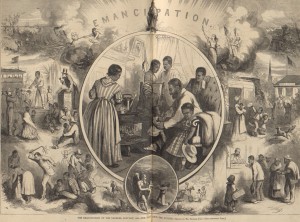

On January 24, 1863, just twenty-three days after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, Harper’s Weekly published Thomas Nast’s radical illustration depicting both this horrors of slavery and his idea of the future of freed slaves. In this original publication, the inscription below reads, “The Emancipation of the Negroes, January, 1863 – the past and the future (Fig. 3).” The composition is organized into three parts: on the left, brutal scenes of enslaved families; in the center, a domestic scene of a black, middle class family under the banner of “Emancipation;” and finally, scenes of education and employment that will define this family’s life in the future.

The drawings on the left of the composition, each of which illustrates the sufferings of the enslaved, suggest the impossibility of normative family units among enslaved persons. The top image shows the brutal hunting of runaway slaves, ruthlessly chased by bloodthirsty hounds and bullets. The center left image shows the separation of a family at a slave auction. An African-American mother, who has just been purchased, begs her new owner to bid on her husband as well, yet the buyer crosses his arms indifferently, unmoved by the woman’s emotion. Her children sit beside her, weeping, as they mimic their mother’s pleading. His stern, callous demeanor is amplified by the juxtaposition of his indifference and her sorrowful emotion. The image’s sympathies clearly lie with the mother and her family and encourage an emotional response to the unjust act.

In the bottom left corner, Nast details a different manner of destroying a family: violent torture. The harsh blow of a whip causes blood to drip from the mother’s bare back. Her children look down, unable to watch as their shackles render them powerless. Just steps away, her husband cries out in pain as a hot iron brands his dark skin. Smoke rises as his flesh is singed. In an adjacent vignette, a white man on horseback raises a long, sharp object above the head of a runaway slave. This combination of imagery undoubtedly elicits the viewer’s sympathy, but it also depicts slave families as fundamentally fragmented, leaving no possibility in the sphere of slavery for mothers, fathers, and children to exist as a family unit.

These illustrations stand in sharp contrast to the central vignette of the work. Here, Nast depicts the future of African Americans as a result of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation presenting African Americans, including a black family, in environments and engaged in activities that would have been perceived as ideal and thus characteristically white. This remains known as one of the earliest published images in which African Americans are shown as normal, civilized and conforming to the conventionally white, Victorian ideal of family.[3] This imagery was particularly shocking to the vast majority of the American population who viewed African Americans as property rather than human. In this new vision for America, black families will live in simple but respectable homes. Mothers will tend to the house, children will go to school, and fathers will work for wages. In one vignette, two young children wave goodbye to their mother as they eagerly join the crowd of black students shuffling into the public school. Below, Nast illustrates an equally unprecedented scene of black laborers receiving pay from a white cashier. To the left of this scene, Nast contradicts the scene that falls on the opposite side of the small circular frame. The same white man on horseback who chased the runaway slave now interacts with a black man in a thoroughly different manner. Although Nast literally and symbolically elevates the white man, all three men, white and black, tip their hats toward one another as a form of mutual respect. Such a comparison suggests that emancipation will create respectful, if hierarchical, relationships between individuals of different races.

In the main scene of this central vignette, Nast produces an image of a free African-American family cast in the image of the conventionally white, Victorian ideal of family. Gathered in their own home, the father laughs as he bounces his youngest child on his knee while the older daughter lovingly grips his arm, pining for his attention. His son holds an open book, denoting his literacy. Although the viewer sees only her back while she prepares a meal at the stove, the mother’s protruding cheekbones indicate her smiling gaze. An elderly woman, presumably the grandmother, rocks in her chair, while a younger couple chats in the background. The representation of multiple generations highlights the notion that this family has remained intact over time.

Without a careful search, Lincoln’s presence could go unnoticed. Nast strategically hangs a photo of the President above the mantel, just below the sizable inscription reading, “Emancipation.” These two inclusions contextualize the image, subtle reminders that the acceptable black family can only exist under the banner of emancipation- not as an inherent right, but a right given to them by white men. Although this engraving aims to depict freed African Americans in a positive light, it does so while upholding the racial hierarchy instilled by the institution of slavery.

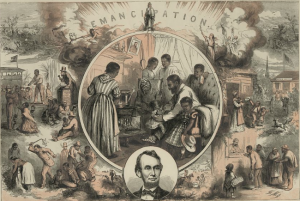

Unsurprisingly, this image became popular amongst abolitionists. So much so, that the illustration was reprinted and distributed as a poster (Fig. 4).[4] The poster that circulated differs slightly from the illustration published in

Harper’s. A portrait of President Lincoln replaces the allegorical scene at the bottom. This version puts Lincoln at the forefront, solidifying his involvement. This combination of sentiment and politics make Nast’s Emancipation and its successor efficacious. Not only does the composition act as an artistic manifestation of a controversial political debate, but it also humanizes African Americans while maintaining racial hierarchy instilled by slavery.

[1] Fiona Deans Halloran, “The Power of the Pencil: Thomas Nast and American Political Art” (PhD diss., UCLA, 2005), 132.

[2] Ibid, 135.

[3] Rob Kennedy and Harp Week, “”On January 24, 1863, Harper’s Weekly Featured a Cartoon about the Emancipation Proclamation.”

[4] Halloran, “Power of the Pencil.”

Works Cited

Dalton, Karen Chambers. “The Alphabet Is an Abolitionist.” The Massachusetts Review 32, no. 4 (December 1, 1191): 545-80.

Editors of The Encyclopædia Britannica. “Thomas Nast | Biography – American Political Caricaturist.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Last modified July 23, 2014. Accessed November 28, 2015. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/404083/Thomas-Nast.

Halloran, Fiona Deans. The Power of the Pencil: Thomas Nast and American Political Art. PhD diss., UCLA, 2005.

Kennedy, Rob, and Harp Week. “On January 24, 1863, Harper’s Weekly Featured a Cartoon about the Emancipation Proclamation.” The New York Times Learning Network. Last modified January 24, 2001.