Just four short months ago, a group of seven intrepid students met in the art history seminar room at Tulane University, charged with curating a virtual exhibition related to the art and visual culture of the Civil War. This project represented the culmination of a course of study upon which they had embarked with me the previous semester, a readings seminar on the same topic rather dauntingly entitled “Contested Visions of the Civil War: Race, Rebellion, Reconstruction, Reunion, Romanticization, Revision and other Narratives in American Art & Visual Culture.” Ostensibly this course—a semester full of critical texts, exhibitions, meaningful field trips (including a weekend trip to visit a number of sites in Atlanta), guest lectures, and, most significantly, lively discourse about all of these—had prepared them to tackle the task at hand. And in terms of content knowledge, the students were, indeed, prepared. However, a critical difference distinguished this semester from the last: this term the students were on their own. Whereas in the fall I had determined the framework and the content of our study, in the spring, for better or for worse (and, I am happy to say, I believe it ultimately turned out for better), I left everything up to them. While the course syllabus provided a rough framework and timeline for working out this “everything” through a series of assignments, they took responsibility for determining the exhibition topic, framing the curatorial vision, selecting objects, generating all of the written content, designing and building the website, even organizing and publicizing an opening event. My contribution: participate in editing process and write this introduction. This exhibition is their achievement.

At the first exhibition development meeting, the student curators came prepared with individual lists of goals for the show (including both objectives they wanted to meet and pitfalls they hoped to avoid) as well as three pitches for topics that they believed lent themselves well to achieving these goals. As with any group enterprise, they had to be prepared to compromise to accommodate others’ visions while also fighting to preserve their own. Rather quickly, points of intersection emerged among the different proposals.

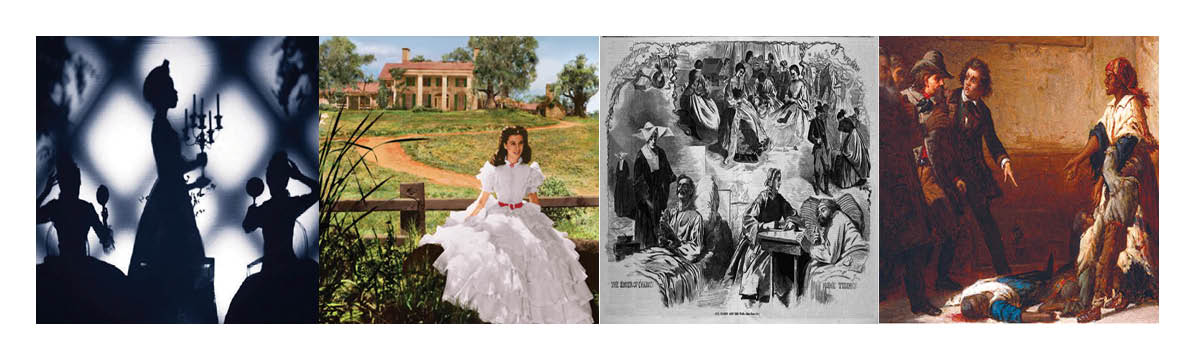

In light of recent major Civil War-related exhibitions like Photography and the American Civil War (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2013) and The Civil War in American Art (Smithsonian American Art Museum 2012) and an assignment that required an analytical survey of Civil War-related museum exhibition catalogues from years past, several members of the curatorial team argued for an exhibition that challenged stereotypical notions of what a “Civil War exhibition” might look like. They urged for something that went beyond images of men—primarily white men—in blue and gray battle uniforms, beyond battlefield photographs, and monuments to Emancipation. Furthermore, the curators agreed that they wanted to develop a show that allowed their viewers to explore a diversity of experiences, attending especially to issues of race, gender, and class in nuanced ways, during the Civil War era—a period that they broadly conceived to include the years leading up to the sectional crisis in antebellum America, the period of the war itself, and Reconstruction. They also wanted to include some reflection upon the continued legacy of this period in the present, especially considering idealized perceptions of the Old South that have had lasting contemporary reverberations. In addition to this conceptual breadth, the curatorial team prioritized the inclusion of a variety of visual materials—so-called “high art” like painting and sculpture, the popular mediums of prints and photography that significantly impacted how Americans saw—quite literally—the war and its attendant concerns, and later advertising and film representations that promoted a very particular vision of the period in the popular imagination. Ultimately, the curators chose representations of women related to the Civil War era as the topic through which to realize their curatorial vision, and it has served them well in this regard, providing the latitude to use a range of visual materials to investigate a diversity of subject matter and experiences across the period and into present through the unifying lens of gender. Each curator selected a group of related objects that allowed them to explore the concerns that the group had identified and developed an essay around those objects.

Beginning with the antebellum period, Rebecca Villalpando offers a provocative discussion of one of famed antebellum New Orleans portrait painter Jacques Amans’s most well-known pictures. Questioning the status of Amans’s Creole in a Red Headdress as a portrait, she astutely analyzes it within the context both of Amans’s more conventional portraits of white female sitters, more conventional portraits of free women of color from the same period, and recent theoretical scholarship about the role of portraiture. Villalpando insightfully observes how popular perceptions of mixed-race women in New Orleans inform Amans’s portrayal of the intriguing woman in this famous picture.

While Villalpando’s work primarily considers images of free women—both white and of color—with the means to commission their own portraits or, at the very least, connections to wealthy men who commissioned portraits of them, Rachel Jolivette Brown’s essay explores representations of a thoroughly disenfranchised set of subjects—enslaved women, specifically enslaved mothers. Considering a variety of material from prints to oil paintings, Brown analyses what these images reveal about period perceptions of black women’s relationship to motherhood, ultimately concluding that African American women could be understood as mothers only when that position was somehow mediated or approved by white authority. Her study also probes the enduring implications of the mammy figure, a black woman defined by her maternal labor but precluded from the actual mothering of black children, as an American cultural icon.

While Brown offers a comprehensive discussion of representations of motherhood and slavery, Tom Strider’s essay explores enslaved motherhood in a more tightly focused way, considering mid-nineteenth-century depictions of the biblical figure Hagar, an Egyptian bondswoman forced to bear her master Abraham’s child and then cast out with her baby into the desert. Strider observes how American artists with divergent political leanings—from the Confederate sympathizing painter John Gadsby Chapman to the abolitionist-backed, Afro-Chippewa sculptor Edmonia Lewis—represented Hagar differently in relationship to period ideals of true womanhood in order to serve their various agendas.

Changing ideals of true womanhood also inform Caylie Zweig’s essay which analyzes visual materials like book illustrations and prints published in popular newspapers to examine the impact of the war on women’s participation in the public sphere. Zweig observes that the war necessitated women’s forays into public participation but that adherence to conventional ideals of gender limited the scope of this participation and determined the way in which it was framed by public discourse. Through an insightful analysis of images, she shows that the war did not really change prevailing notions about the nature of woman or the duties—primarily domestic—for which she was made, but it did change the arena in which she could acceptably operate, and this change, importantly, outlasted the the war itself.

Like Zweig, Sarah Senette also considers how the war created unprecedented opportunities for women’s public participation. Taking the exhibition into the post-bellum period, Senette’s essay uses a variety of images to explore how a diverse set of constituencies—former Confederate Southern women, white and black Northern female reformers, and formerly enslaved women—all worked to realize their vision of the South after the war. Senette pays careful attention to how the dynamics of race, class, and status as simply free or newly freed informed how these women saw themselves and imagined the postwar South. Though these women envisioned very different, indeed diametrically opposed, southern societies, they all embraced their roles as agents in realizing that vision.

In her discussion of the women of the former Confederacy, Senette discusses the powerful ideology of the “Lost Cause” through which the South worked to recuperate its image, and a romanticization of the “Old South” undergirded this ideology. In her essay, Sarah Monaco explores the postwar construction of the Southern Belle as a popular culture icon who exemplified this idealization of antebellum plantation life. Moving the exhibition beyond the nineteenth century, Monaco considers the Southern Belle as a post-bellum fiction who helped sell the image of the Old South even as that image was used to market goods like cosmetics to American consumers. Analyzing popular culture images like promotional photographs for the 1939 blockbuster film, Gone with the Wind (a distorted telling of the Civil War narrative far more popular than any history book) and print advertisements for luxury goods like perfumes, Monaco explores the enduring legacy of the image of the Southern Belle and the picture of antebellum America she promotes.

Elizabeth Leavitt also considers this enduring legacy but in a different context. Leavitt investigates how the relations of power relating to race and gender that prevailed in the South after the Civil War informed and continue to inform the traditions of Mardi Gras, arguing that the Mardi Gras queen should be understood as a local iteration of the Southern Belle who who elevates the status of the Belle to the level of royalty. Analyzing a diverse array of visual materials, beginning with an 1892 portrait of Winnie Davis, daughter of Confederate president Jefferson Davis, in her regalia as the Queen of Comus and ending with a photograph by contemporary African American photographer Carrie Mae Weems that offers a bold raced and gendered critique of Mardi Gras traditions and directly references a racist costume design from Comus’s 1873 parade, Leavitt convincingly asserts that the dynamics of race, gender, and power that shaped the post-bellum and especially the post-Reconstruction South continue to inform Mardi Gras tradition in the present.

Each of the essays provides a focused study of some aspect of women’s representation during the Civil War era; taken together, they explore the diversity of this representation from the antebellum period through Reconstruction and its lasting impact into the present day. While, governed by their own interests related to the exhibition theme, the curators wrote these essays and the corresponding image discussions as individuals, all of the written content for the exhibition was peer workshopped and edited and went through extensive revision. They enthusiastically supported each other through the process, offering constructive critique and generous praise. From Slave Mothers & Southern Belles to Radical Reformers & Lost Cause Ladies represents a remarkable achievement by a group of emerging young scholars with whom I have been very privileged to work. I hope you will agree that this work constitutes an impressive accomplishment and encourage you to leave comments for the curators.

Mia L. Bagneris

30 April 2015

Congratulations to Professor Bagneris and her students! This is a great showcase not only of the artwork, but of student research and engagement at its best. And what exemplary public scholarship!

I have greatly enjoyed Strider’s writing on the Two Treatments of Hagar. I hope to explore the website more, and have referenced this in some of my recent work. Thank you to all the curators and to Prof. Bagneris for this excellent project!