African American Teachers in the Aftermath of the Civil War

“Words Can Give You No Idea”[1]

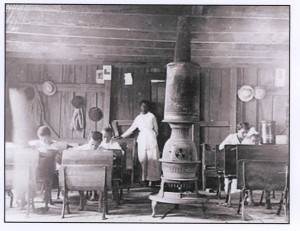

The young woman in Interior, African American Schoolhouse rests one hand authoritatively on a nearby chair. Chin held high, she gazes unabashedly at the viewer. Rows of students, heads bent over their books, create diagonal lines emphasizing her place in the center of the image (figure one). Dusty floorboards and the low-slung ceiling create strong horizontal panels on either side of the image, framing the scene. The interior itself appears a study in vertical lines, with the young women in the center behind a large pot-belly stove. While the stove radiated heat, the young woman radiates a different kind of energy that likewise fills the space. Dressed in pristine white, the young woman is more than a focal point. She appears to hold the entire composition together. In a sense, her position of importance in the overall composition of the image conveys historical fact far better than what most historians have written about African American education in the Reconstruction South.[2] While historically overlooked, many African American women from the North journeyed to the South following the Civil War and – often at great personal risk to themselves— taught newly freed slaves.

Virginia Historical Society’s exhibition: the Civil Rights Movement in Virginia, 2004, Web site: http://vahistorical.org/civilrights/education.htm#images

Library of Congress, Prints and Photograph Division, Washington D.C. USA.

In addition to the bold stance of the unnamed woman in white, Ester Douglas’ diary also tells the viewer of one African American teacher’s courage in choosing to brave the poverty, devastation, and violence of the South in the years following the Civil War. Douglas remembered that “bones of cattle and horses, and twisted rail” lined the roads.[3] Moreover, some of the newly freed students went without clothes, covering themselves with blankets, and Douglas herself received death threats from local members of white supremacy groups. On one memorable ride into town, Douglas’ white driver “enlighten[ed]” her “with stories of the KKK’s doings as [they] passed the places where there had been whippings and hangings.” When Douglas boldly suggested that the law should be in charge of punishment, her driver replied that “no nigger ever got more than he deserved.”[4] The fact that Douglas, in addition to other African American teachers in the South, often worked in such dreadful environments suggests their commitment to educating African Americans and faith that, through education, they could impact change. In light of first hands accounts, such as the Ester Douglas,’ the unnamed woman’s strong stance in Interior, African American Schoolhouse adopts a heroic quality. The order of her classroom could easily be in direct opposition to violent chaos of the outside world and her stance in front of the school-room door one of protection over her students. [5]

Interior, African American Schoolhouse, supports Douglas’ recollections of the difficulties faced by African American teachers during Reconstruction. Both the walls of the schoolroom and the floors are bare except for a few hats and coats hung in no particular order. There are few class supplies and the light in the image comes from a single source, suggesting only one window. Like most of the ‘children’ in African American schools, the students range in age from the very young to fully adult. Indeed, the authoritative young woman in white may not even be the teacher, despite her age. Other images from the period support the assertion that older African Americans during Reconstruction also sought education when it became available. In The Misses Cooke’s Schoolroom, Freedman’s Bureau, there appears to be an adult man in one of the first rows (figure two).

Jas. E. Taylor. Illustrated in: Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper, v.23, 1866 Nov. 17, p. 132. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. USA

Aside from possibly depicting an adult student, The Misses Cooke’s Schoolroom strays very far from historical reality. The children and the teachers are well-dressed, and, while the teachers may have been able to procure nice clothing, the newly freed children would likely not have had this luxury. Unlike Interior, African American Schoolhouse, the classroom in The Misses Cooke’s Schoolroom has multiple windows, a map on the back wall, and even a rug by the furnace. Moreover, the extended line of the ceiling boards next to the stone chimney indicates that school in The Misses Cooke’s Schoolroom is at least two rooms. The most notable contrast between the two images, however, is that the schoolmistresses in The Misses Cooke’s Schoolroom are white. While many white women missionaries did teach newly freed slaves after the Civil War, their tenure was generally very short and they rarely lasted beyond three years. Furthermore, “northern African Americans participated in the education of their race at a rate twelve to fifteen times greater than northern whites” and “more than one third of all teachers in southern black schools between 1861 and 1876 were African American.”[6] African American school teachers often continued to teach for decades, even when faced with death threats. This dedication can be explained in part because African American teachers’ purposes “were grounded in a lifelong dedication to the uplift of their race in all facets of life, and especially through education.”[7] This connection to the racial uplift movement helped bolster African American teachers as they believed that education was a key component in racial equality.[8]

Interior, African American Schoolhouse makes evident the tenacity and fortitude of African American school teachers in the Reconstruction South. Unlike the somewhat serene poses of the white women in The Misses Cooke’s Schoolroom, the unnamed young woman in Interior, African American Schoolhouse emanates firmness and energy. She seems unintimidated by cracks in the schoolroom walls, and the student’s simple clothing— both of which would have been normal for African American schools during the latter years of Reconstruction.[9] Akin to Douglas’ fearless journey into a stronghold of white supremacy, the unnamed schoolteacher metaphorically appears a pillar of strength. All in white and with fully erect posture, she embodies the notion of a pillar holding up the school. However, like the way in which history remembers African American teachers’ during Reconstruction, she is also in the background.

SJS

[1] Ester Douglas, Diary Exert, Ester W. Douglas, 1887, North Carolina, Tulane University, Amistad Research Collection, Box 9, folder 2, page 4.

[2] Wilma King, The Essence Of Liberty: Free Black Women during the Slave Era (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006) 187; Heather Andrea Williams, Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 4,5,7-9.

[3] Douglas, Diary Exert, Ester W. Douglas, 1887, page 4.

[4] Ibid. 50.

[5] Ronald E. Butchart, Schooling the Freed People: Teaching, Learning, and the Struggle for Black Freedom, 1861-1876 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), xi-xiii, xv.

[6] Ibid., xiii.

[7] Kay Ann Taylor, “Mary S. Peake and Charlotte L. Forten: Black Teachers During the Civil War and Reconstruction,” The Journal of Negro Education 74, no. 2 (Spring, 2005): 125.

[8] Ibid., 124-126.

[9] Williams, Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom, 80-84.