Tom Strider

In the history of western art representations of the biblical Hagar endure across centuries. Major European artists depicted a variety of events from the traumatic story of the enslaved Egyptian mother of Abraham’s first son Ishmael. Among these Salvator Rosa, Veronese, and Giambattista Tiepolo contributed to the standardization of the particular scene of Hagar and Ishmael in the Wilderness (Genesis 21:8-19).[1] After Hagar’s banishment by the patriarch into the desert, at the moment when Ishmael is dying of thirst, God hears his crying and responds by leading Hagar to a spring of fresh water. The artists often portray the outcast “fallen” woman in a sympathetic light, accompanied by her most frequent attribute, an overturned jar. Well into the nineteenth century, Camille Corot (1796-1875) continued this pictorial tradition of the inclusion of an angel in his vast desolate landscape version of the scene (fig.1).

However in the nineteenth-century, American artists frequently departed from the tradition by placing a primary focus on the figure of Hagar. Ishmael shifted in compositional importance and the angel faded from popular usage. The emphasis on Hagar in emotional turmoil derived from diverse interpretations and applications of the constructed ideals of true womanhood—grounded in the private domestic sphere—that dominated the antebellum and Civil War periods.

This essay examines a number of artworks featuring Hagar (and, in some cases, Ishmael) to demonstrate the surprising adaptability of the subject by different constituencies. During the mid-nineteenth century, John Gadsby Chapman (1808-1889), William Rimmer (1816-1879), and Edmonia Lewis (c. 1844-1907) all explored the theme with a moral objective to stimulate compassion for the ostracized mother, yet the sympathies of each artist aligned with Confederate, Republican, and antislavery concerns respectively resulting in different treatments of the subject.

During the nineteenth century the name Hagar grew in usage, increasingly attached to both black women and references to slavery.[2] Her story reveals the vulnerability of enslaved women to sexual exploitation and the denial of patriarchal protection for themselves and their children. Notably Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) contains a character, Aunt Hagar, tragically separated from her children by slavery. In addition nineteenth-century culture typically associated Egypt, the biblical Hagar’s homeland, with blackness. Despite these associations, Chapman, Rimmer, and Lewis—like western artists before them—depict Hagar with European features. Here the similarities end, however. Although the pieces by Chapman and Lewis were executed in Europe, they make evident, strong attachments to contemporaneous American social and political concerns, which Rimmer also addresses. This grouping of artworks, identical in theme, demonstrates how the biblical Hagar was co-opted by proslavery, Unionist, and abolitionist forces to reinforce differing agendas.

In the context of strict social mores of the period, these perhaps surprisingly empathetic portrayals help define the parameters of a concept of ideal womanhood that dominated much of the century. Of the many variations on the story that occur in the history of western art, artists most commonly depicted two: Hagar and Ishmael’s expulsion from the household of Abraham and the scenes in the wilderness.[3] The former emphasizes the immoral sexuality of Hagar, while the latter allows for her deliverance as a nurturing, loving mother.[4] Most nineteenth-century artists opted for a wilderness setting that emphasized the suffering position of Hagar who submits to forced dependency on a patriarchal society.[5] The repeated use of the empty overturned jar, subverts a common feminine symbol, by suggesting the inability of enslaved or abandoned mothers to effectively provide a nurturing, protective environment for their offspring.

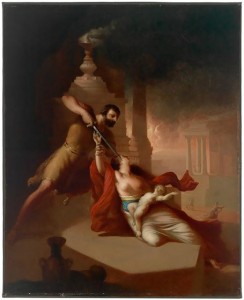

If studying and working within the country, young nineteenth-century American artists had limited access to European works that depicted the theme. One important work that earned public display was Benjamin West’s (1738-1820) painting of Hagar and Ishmael (1776) that hung in the Philadelphia Academy from 1851-1864. (fig.2)[6]

The picture, created at the beginning of the Revolutionary War, represented the Egyptian mother as more forthright. Unlike later nineteenth-century depictions, nudity and diffidence and are not part of her representation. Only her hands and face are uncovered. Considering the time of execution this Hagar reflects more the possibilities afforded a new American nation freed from English domination: “And of the son of the bondwoman will I make a nation, because he is thy seed.” (Genesis 21:13) Her head covering may be a Phrygian cap, attire typical of Republican Columbian symbols of the period. While Ishmael appears anguished and dehydrated, Hagar remains calm and thoughtful. An angel floats above the pair and points in the direction of a water source. A dark color scheme of gold, rust, and blue evokes a stormy environment.

Chapman’s Hagar and Ishmael

Virginia artist John Gadsby Chapman created his first major painting Hagar and Ishmael Fainting in the Wilderness while studying in Rome in 1830 (fig.3).

The first American picture to be engraved in Italy, it subsequently appeared, in the same year, in the Giornale de belle arti ossia pubblicazione mensuale della migliore opere degli artisti moderni Roma.[7] Virginia-born Louisiana cotton broker John Linton (1786-1834), who had financially supported Chapman’s three-year European sojourn, was named in the journal, and the painting appeared in his New Orleans collection by 1832.[8] Afterwards, the painting disappeared from the art historical record. The recent discovery of this seminal picture provides an opportunity to place it, and other Chapman works, within the context of the antebellum concept of “true womanhood” that dictated piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity for all women.[9]

The picture’s muted color scheme of gold, umber, and rose reflects the young artist’s response to European influences in subject, costume, and drapery. As previously stated, the empty water jug in the foreground identifies the despondent subject as Hagar. The seated Hagar rests her right upper arm on a rock while her hand supports her head in a gesture that evokes extreme fatigue, fear, anger, and sadness. Her other arm drops to her lap and cradles her young son’s head and hand in a gesture of tenderness. Her parted lips and eyes are raised heavenward in desperation. Ishmael’s expression is resigned and his fist, resting on a rock, provides one of the lovelier visual passages. The tenderness expressed in tactile qualities created where the boy’s cheek, hand, and her hand touch contrasts with the stony hardness of their surroundings. Hagar’s costume, with its laced bodice and white chemise, in addition to her braided hair, appear more European peasant, than biblical, in origin. Reflecting classical influences, both figures have bared shoulders that suggest the vulnerability of their situation. The pyramidal shape of the combined figures adds to the overall feeling of emotional weightiness. Though surrounded by dark clouds, in a sign of hope, a theatrical light bathes the figures from above.

John Linton married into the prominent cotton growing Surget family of Adams County, Mississippi. That the painting came to reside with a family of Mississippi planters creates a fascinating conundrum. As stated earlier, in the nineteenth century, the figure of Hagar often symbolized enslaved African-American women. It’s difficult to imagine Chapman, a Confederate sympathizer, or Linton, a planter’s agent, viewing the subject from this perspective: why then did the subject appeal to them? Considering Chapman’s treatment of Hagar in light of the artist’s best-known work, The Baptism of Pocahontas, located in the Rotunda of the U. S. Capitol building, suggests a possible explanation. The epic painting depicts the first conversion of an American Indian to Christianity. Many of Chapman’s works have religious themes, and it may be possible to view his treatment of non-European women, including the Egyptian Hagar, from an idealized Christian perspective. Both pictures suggest that non-white women should follow the dictates of white culture, and that Christians have a moral duty to share, often forcibly, their religious beliefs. This civilizing responsibility lent the proponents of slavery a defense against an otherwise shameless institution. Chapman permits the redemption of Hagar by emphasizing her deference to God and her motherly devotion to Ishmael. By making the subjects white, he may have simply been following a prevailing tradition or responding to the perceived desires of his patron.[10]

Rimmer’s Kneeling Hagar

William Rimmer (1816-1879) created his Hagar and Ishmael amidst the heated political debate over slavery shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War and the painting should be understood in the context of his Republican political leanings (fig.4).

In addition to painting, Rimmer was a practicing physician in Massachusetts, and the artist mixed in liberal abolitionist circles. Another picture by the artist Massacre of the Innocents, created about the same time as Hagar, sheds light on his political sympathies (fig.5).

In this dramatic scene he adopts a familiar abolitionist trope that links the Biblical King Herod—who ordered the wholesale slaughter of Jerusalem’s newborn males—with powers that work to keep the system of slavery intact. In the picture Herod’s agent, a fierce, sword-wielding soldier draws his weapon to attack the babe of a mother draped in red, white, and blue clothing. Abolitionists viewed slavery as not just as an injustice served on African Americans, but as a threat to American civilization.[11]

Rimmer’s Hagar kneels in a rocky landscape and her face, with eyes cast upward shows anguish and exhaustion. The faintly painted figure of Ishmael lies in the background with his back arched upward as if gasping for breath. Hagar’s loose brown hair flows behind her and frames an oval face with overly large eyes. Details of her dress, including gold bracelets and the gold trim of her ultramarine drape, hint at her exotic status and the refinement of her former existence. Her delicate, clasped hands rest on a rock, with fingers knotted in anxiety. Hints of green and blue define the surroundings as landscape, but in the overall color scheme of umber and sienna, the background appears both parched and tempestuous. Her cloak flows out behind her figure forming a triangle, her head at the top. Her shoulders are bare, and a scalloped bustier reveals a smooth white chest. The positioning of the figures references the Genesis account of Hagar’s placement of the child at a distance so that she will not see him die.

Rimmer’s treatment of the beleaguered mother exposes the malignant effects of slavery’s frequent dismantling of families. Banished by Ishmael’s father, Hagar is unable to perform her maternal responsibilities as a true woman: to preserve and protect a domestic environment. This denial of the ideal results in anguish. The depiction suggests that by threatening the patriarchal family, slavery also undermined the moral fabric of the republic.

Lewis’ Hagar

In 1868 (or possibly in 1878) Edmonia Lewis, an American sculptor of African American and Chippewa origin, also took on the subject of Hagar (fig.6).

Lewis associated with a progressive elite that included Lydia Child, William Lloyd Garrison, and the Shaw family, and the artist often chose subjects to appeal to these abolitionist patrons. Notable are portrait medallions of Garrison, John Brown and the figure group Forever Free. Considering Lewis’ sculpture in light of this and the nineteenth-century association of Hagar with enslaved African American women supports an anti-slavery interpretation of the work. She studied with the sculptor William Brackett and created portrait busts to earn money for her relocation to Rome.[12] Lewis broke new ground by obtaining international acknowledgement for her work as an artist. The first nonwhite artist to achieve this level of success in sculpture, she frequently chose subjects that reflected her dual ethnicity and gave expression to anti-slavery and American Indian concerns.

Other American artists working in Italy also embraced the theme. Several years earlier Edward Sheffield Bartholomew (1822-1858) sculpted his own version of the subject Hagar and Ishmael in a sophisticated bas-relief of 1856. (fig.7)

Of all the depictions discussed here, Bartholomew’s is the most reflective of classical origins. The carved marble’s flowing, almost liquid drapery, and theatrical sense of tragedy, evoke the Greek funerary stele. Hagar is shown in profile, fraught with anguish and attempting to stand, while her despondent child clings to her waist. The figures form an elongated triangle similar to Chapman’s successful composition where God is suggested at the top of the pyramidal scheme. Ishmael’s right foot and Hagar’s left elegantly form the base of the triangle, with the empty water bottle at the base. Supported by a plinth the figures create the effect of classical sculpture. Hagar’s left arm is raised to her shoulder but the action is unclear, perhaps she attempts to preserve her modesty by keeping her garment in place. Ishmael’s lower body turns toward the viewer while his anguished mother remains in strict profile. Heavy folds of drapery and the fact that none of the subjects’ feet are firmly planted weight down the action. Hagar’s long hair cascades down her back, the movement of curls progresses in the dips of drapery moving down her rear and thigh. Ishmael face is downcast. Bartholomew shows a Hagar weighted down by the demands of mothering an out-of-wedlock child.

Bartholomew’s rendering provides a transition to later representations of more independent and assertive women that appear in works such as those of Edmonia Lewis. As a young sculptor, Lewis had joined a sizable community of women artists in Rome in 1865. Like Chapman and Rimmer, Lewis depicts the Biblical Hagar at the moment she encounters God in the desert. Her representation of Hagar (1868 or 1875) in marble shows her alone and upright and on the verge of moving forward. Though in obvious distress, her clasped hands indicate independent resolve as much as they do prayer. Firmly planted, her left foot carries the weight of the figure while the right one, pushes off the ground behind her, thereby suggesting imminent propulsion. The artist presents her subject in the neoclassical style typical of the period, accompanied by the overturned water pitcher. Curiously, Lewis excludes Ishmael from the scene, though most artistic renderings of the period include him.

Thick wavy hair, parted in the middle, frames an oval face, from which eyes gaze outward to God. Her small closed mouth and straight nose appear ethnically European. Her dress consists of a simple tunic, gathered at the waist. The skirt pulled up on the left side, results in an uneven distribution of fabric that implies an adjustment made out of necessity and anxiety. She wears plain sandals while her calves, right shoulder, and right breast are bare. In a classicizing effect, the animated folds of drapery in her skirt ripple and flow backward while also clinging to her abdomen, thereby revealing the contours of her thighs. The pose exhibits a restrained contrapposto as the weight of the figure seems distributed between both legs and the shoulders and hips are fixed in relation to the figure’s central axis. The interplay of the oppositional

In her choice of Hagar as a subject the non-conformist Lewis examined the futility of maintaining a stable family unit under slavery, a condition that all but insured the impossibility of mothers to adhere to the period constructs of true womanhood. Hagar bore a child through sexual relations with her master, an action that resulted in expulsion from his household. Thus Hagar wanders—violated, homeless and unable to protect her child—and her uncertainty emerges in the conflicted pose of the work. In writing about the piece, art historian Kirsten Buick emphasizes its potent symbolization of the suffering and humiliation of enslaved African-American women. Buick argues that while Lewis’ women are executed in white marble with European features, they nonetheless represent the artist’s determination to broaden the typical range of female subjects in art and the ideals of true womanhood, to include those of non-European origin.[13] While it was not uncommon for all female sculpted subjects to possess the idealized features of classical Greek sculpture, Buick sees the work as racially cleansed in order for the artist to achieve acceptability and to maintain authority over her own expression. By omitting Ishmael from the composition, Lewis placed the focus squarely on Hagar as a woman, and by freeing the work from the probability of biographical interpretation; she allowed her sculpture greater universal implications. [14]

Conclusion

The adaptability of Hagar as a subject allowed an array of artists to examine the question of slavery without confronting it directly. For a variety of reasons these pictures and sculpted figures, created to meet the conservative tastes of patrons in the North and South, removed blackness from the subject’s profile. The works by Chapman, Rimmer, and Lewis when chronologically arranged, show Hagar moving from a seated position that suggests a complete lack of agency, to a kneeling position of prayerful pleading, to standing figure ready to take a more active role in her fate. These differences, while subtle, reflected changing attitudes regarding the roles of women in both public and private spheres.

[1] Previous to the depicted incident, Sarah, Abraham’s wife, abused the pregnant Hagar causing her to flee into the desert. Even though Hagar suffered mistreatment, God found and instructed her to return to Sarah and serve her willingly. Later, Sarah gave birth to a son Isaac. She subsequently perceived Hagar and her offspring as a threat and successfully sought their removal.

[2] Janet Gabler-Hover, Dreaming Black/Writing White: The Hagar Myth in American Cultural History, University of Kentucky Press, Lexington, 2000, 11.

[3] Other representations include: Sarah presenting Hagar to Abraham, Hagar’s return, and conjugal scenes with Sarah as a voyeur.

[4] Gabler-Hover, 7.

[5] Gabler-Hover, 18.

[6] Gabler-Hover, 12.

[7] Ben L. Bassham, Conrad Wise Chapman: Artist & Soldier of the Confederacy, Kent State University, (Kent, Ohio & London, 1998) 6-7.

[8] Surget Family Papers, (Z 1496.000 M) Mississippi Dept. of Archives and History, accessed online.

[9] Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860,” American Quarterly, 18, Issue 2, Part 1, (Summer, 1996), 152.

[10] The subject remained important for Chapman and he painted a new version of Hagar and Ishmael in 1853, keeping it with him for the remainder of his life.

[11] Randall R. Griffey, “Herod Lives in This Republic” Slave Power and Rimmer’s Massacre of the Innocents, American Art, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Spring 2012), University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, 112.

[12] Theodore E., Stebbins Jr. et al., The Lure of Italy: American Artists and the Italian Experience 1760-1914. (New York: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 241.

[13] Kirsten P. Buick, “The Ideal Works of Edmonia Lewis: Invoking and Inverting Autobiography,” American Art, 9 (Summer, 1995) 10-11.

[14] Buick, 14-15.