During the Civil War, some women completely broke out from prescribed gender roles and put themselves in the midst of war. One of these women was Loreta Janeta Velazquez. Velazquez, a native Cuban, went to school in New Orleans, but ran away to marry an officer in the United States Army.[1] After the outbreak of the Civil War, her husband resigned his commission to join the Confederate Army, and Velazquez determined to join him. Finding the battlefront no place for a lady, her husband disapproved. Still, Velazquez defied him, found uniforms, and formed a new identity as a man in order to fight for the Confederate cause.

In The Woman in Battle, Velazquez published a written and illustrated account of her endeavors. These illustrations were fromseparate pages of Velazquez’s book, but here shown side-by-side to highlight the similarities and differences between Loreta Janeta Velazquez and her “male” counterpart. The left part, entitled “Harry T. Buford 1st Lieutenant Independent Scouts C.S.A.”, shows a portrait of Velazquez’s alter ego. Buford wears what is presumably a lieutenant’s uniform. It shows two rows of two buttons and the start of a third row. A typical lieutenant coat has nine buttons per side, in clusters of three each.[2] The visible buttons imply a similar pattern. Buford also wears a military hat and has gentlemanly facial hair. The other image, “Madam Velazquez in Female Attire” shows Velazquez wearing a feminine dress with a bow and a lace collar. Her hair is put up and conservative. The label “madam” highlights the disparity between the gendered titles and emphasizes her womanliness. Both faces have similar expressions, yet their features are slightly different despite actually being the same person. Buford has thicker, manlier eyebrows than Velazquez. Velazquez’s eyes are wider and brighter, perhaps a metaphor for her forward way of thinking and acting. Ironically, Buford has softer and more womanly facial features than Velazquez, such as his supple skin and button nose; perhaps the artist’s attempt to make Velazquez’s sex apparent to the reader despite her male attire. However, one would not necessarily know that Buford is really a woman by just looking at the picture. Velazquez as a woman has wrinkled skin and a long, thin nose. Her older looking skin may be an implication of an age difference. The book looks at her life in retrospect, so the image of Velazquez shows her later in life, while the image of Buford depicts a more youthful state. The swap of typical male and female features parallels Velazquez’s subversion of gender roles and her foray onto the battlefront.

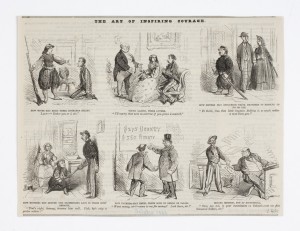

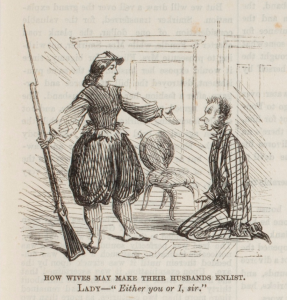

In Frank Leslie’s “The Art of Inspiring Courage” the top left graphic shows a scene related to Velazquez and her husband’s story. The sketch shows a husband and wife with a caption that reads, “How wives may make their husbands enlist. Lady- ‘either you or I, sir”. The woman, in her bloomers, stands over her kneeling husband, with one hand gesturing towards him and the other holding a musket. The man has a look of disgust on his face brought upon by the thought of his wife enlisting; similar to the disapproval Velazquez’s husband must have felt when she wanted to join the army. The man in this case has to be the hero for his wife to preserve her respectability. This cartoon preserves the ideal of women staying in the domestic sphere and not venturing into public or dangerous fields, however it also has progressive feminist undertones. At the time, there was much controversy about women’s dress. Here, the woman’s outfit connotes advancement in women’s fashion that had women wearing clothing similar to those

previously only worn by men. In a movement spearheaded by reformers such as Amelia Bloomer and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, women started to wear trousers in public and attempted to eliminate the stigma associated with this attire.[3] She also wears a military cap, which shows she is serious about her statement that she would enlist if her husband did not. In this image, the woman stands and takes control of the situation while her husband passively sits on his knees and listens to her.

Unlike Velazquez, the woman in Leslie’s sketch upholds period gender norms, invoking her privileged femininity to coerce her husband into joining the army, yet her attire hints at progress. Velazquez genuinely wanted to join for herself and rebel against the standards set for women at the time. She effectively did so, since she successfully fought in many Civil War battles and eventually became a Confederate spy.

[1] “Summary of The Woman in Battle: A Narrative of the Exploits, Adventures, and Travels of Madame Loreta Janeta Velazquez.” Documenting the American South. Accessed February 23, 2015. http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/velazquez/summary.html.

[2] “Uniforms of the Confederate States Military Forces.” Wikipedia. Accessed February 25, 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uniforms_of_the_Confederate_States_military_forces.

[3] Patricia A. Cunningham, Reforming Women’s Fashion, 1850-1920: Politics, Health, and Art (Kent State, 2003). 33.