Caylie Zweig

Loreta Janeta Velazquez defied gender norms during the Civil War and boldly faced the battlefront. Velazquez lived in Texas with her husband and was eager to persuade him to let her fight for the Confederacy. When he refused, she ignored him, dressed up as a man and took on the name Harry T. Buford. Velazquez gave herself the rank of lieutenant and gathered volunteers. Velazquez’s account of her endeavors, The Woman in Battle, included portraits on separate pages here shown side-by-side to highlight the similarities and differences of Loreta Janeta Velazquez and her “male” counterpart. Ironically, Buford in this illustration has softer and more womanly facial features than Velazquez. A cap of soft curls tops a supple-skinned face with dreamy, dark eyes, round, full cheeks, and a button nose. These feminine features might represent the artist’s attempt to hint at the female body beneath Burford’s facial hair and military uniform. Contrastingly, when presented as a woman, Velazquez has haggard skin and much sharper, more masculine features. Her face is defined by a severe coiffure, her hair pulled tightly back to expose a light-eyed, piercing gaze, a thin, beak-like nose, and a square jaw. Despite the frilly lace at her throat and the bow at her neck, the artist renders Velazquez as stoic and resolute, a woman with the fortitude for battle. This swap of typical male and female features echoes Velazquez’s subversion of gender roles and her foray onto the battlefront.

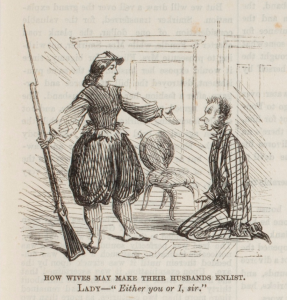

In Frank Leslie’s “The Art of Inspiring Courage”, a cartoon of northern origin, the top left graphic shows a scene reminiscent of Velazquez’s and her husband’s story. The sketch shows a husband and wife with a caption that reads, “How wives may make their husbands enlist. Lady- ‘either you or I, sir”. The woman, in her bloomers, stands over her kneeling husband, with one hand gesturing towards him and the other holding a musket. The man has a look of disgust on his face brought upon by the thought of his wife enlisting; similar to the disapproval Velazquez’s husband must have felt when she wanted to join the army. The man in this case has to be the hero for his wife to preserve her respectability. This cartoon preserves the ideal of women staying in the domestic sphere and not venturing into public or dangerous fields. She also wears a military cap, which shows she is serious about her statement that she would enlist if her husband did not.

Unlike Velazquez, despite threatening to join the war effort on the battlefield, the woman in Leslie’s sketch upholds period gender norms, invoking her privileged femininity to coerce her husband into joining the army. While Velazquez did exactly what the woman in the cartoon only threatened, successfully fighting in many Civil War battles and eventually becoming a Confederate spy, her case is not the norm. Much more common were women– Northern and Southern– who performed tasks, such as nursing, that blurred the lines between the domestic and public spheres. This essay examines the representation of such roles in Civil War era visual culture.

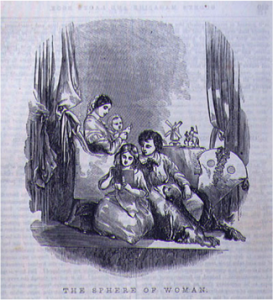

In March 1860, Godey’s Lady’s Book displayed an illustration called “The Sphere of

Woman,” in which a mother and possibly a nanny sit with two children in what appears to be the children’s nursery, a place in which the ideal woman would have been expected to spend plenty of time. The title refers to the domestic sphere, which is “private-encompassing the unregulated realm of home, family, and child rearing.”[1] Both older women interact with a child, one reads to the daughter while the other tends to the baby. Ideally, antebellum women behaved like the women in this sketch centering their lives around home and family; however, changes in women’s roles during the war changed this representation of the ideal woman, moving women’s “domestic” activities into the public sphere.

During the Civil War, the sharp dichotomy between the public and private spheres for women started to diminish especially for white, middle-class northern women and white, upper-class southern women who had been expected to conform to idealized prescriptions of womanhood. Performing more traditionally feminine tasks but in the public sphere during the war, women started to break free from their previously prescribed gender roles, a fact which had a lasting impact on the participation of women in the public sphere.

Northern Women

When men left for war, the survival of individual families and wellbeing of both the North and the South depended on women’s increased roles in the public sphere. Most often, they took on work that required skills similar to those they used as homemakers. Toward the beginning of the war, women started unifying to help the war effort in any way possible. Northern women worked under the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) and the Women’s Central Agency of Relief (WCAR), both organizations responsible for fundraising and gathering donations for the war effort. Also, numerous “women saw that many of the activities they had done at home had financial value,” so they used their domestic abilities to benefit those outside their own home. [2]

After the 1861 attack on Fort Sumter, Northern women immediately prepared to support the Union cause by organizing items for the troops, creating sewing circles, and volunteering as nurses.[3] Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the nation’s first female physician, and others established The Women’s Central Association of Relief (WCAR) to organize these groups of female volunteers. The WCAR then turned into localized branches of the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC).[4] The success of the USSC depended greatly on women as is evident from the angelic female figure caring for fallen men on its seal. A beautiful woman literally descends from the heavens to save these men, just as many women who were previously angels of their homes came to save real wounded soldiers. [5]

As the USSC seal suggests, although women took on many types of jobs, they were best known for the types of stereotypically domestic jobs performed by the USSC and also shown in Winslow Homer’s “Our Women in the War, “ published in the September 6, 1862 edition of Harper’s Weekly. In this engraving, the multiple vignettes show women bringing the comfort of the home front to the soldiers of the battlefront while captions underscore the domestic nature of their public participation.

In Homer’s image, women perform assorted tasks. A nun in the vignette on the bottom left provides a bed-ridden man with a rosary, offering spiritual support and healing. Underneath, the text reads “the sister of charity” to reinforce that she is in fact a woman with the exclusively female job of a nun. In the scene on the lower right, a bonneted woman writes a letter as a helpless-looking man dictates. Homer labels the scene “home tidings” and emphasizes the role of the letter-writer as the soldier’s connection to home. Without her help, the soldier would not be able to communicate with his family, emphasizing her role between the domestic and public spheres. In two separate vignettes at the top of the composition a woman hangs military laundry as under the supervision of a soldier and a sewing circle makes clothing for soldiers. Previously, women performed these jobs at home, but now they do them in the context of the battlefront. By showing women as nurses, seamstresses, and in other traditionally feminine roles, Homer makes woman’s foray into the public sphere palatable for the viewer.

All of the figures in Homer’s image have slightly obscured and anonymous faces. Not one female figure faces the viewer directly. All have generic features and many are in the shadows. This makes it so that any woman could see herself in these roles and was likely meant to inspire women to join the war effort, especially since Harper’s Weekly reached many audiences. On the other hand, this strategic move also trivializes the very real accomplishments of individual women, making their contributions seem less important than if Homer had decided to create portraits of such individuals.

Across the top of the image, arced text reading “the influence of woman” softens the top corners of the image. The text that accompanies this image in Harper’s Weekly says, “this war of ours has developed scores of Florence Nightingales, whose names no one knows, but whose reward, in the soldier’s gratitude and Heaven’s approval, is the highest guerdon woman can ever win.” On the surface, the pairing of these texts with the image relay optimistic messages about women and the war. The top text, especially in conjunction with the images, posits women’s positive influence on the war. When both texts are paired together, however, the subtext is less encouraging, implying that women are only capable of this kind of traditionally feminine work. By asserting that the reward of appreciation from soldiers is “the highest guerdon woman can ever win”, Harper’s implies that women live to serve men and the best reward they can receive is male gratitude and God’s approval. Additionally, the text references Florence Nightingale, a real successful woman, yet she is used as generic shorthand referring to a type of woman instead of for her specific and important accomplishments. Homer’s work both honors women’s new working roles and sets restrictions for the types of work that women should perform. At a time when women’s roles changed, “Our Women in the War” praises this change, yet simultaneously limits the scope of possibilities for progress.

Southern Women

Like northern women, southern women took on many new roles. “Off for the War” shows a family from Winchester, Virginia sending the father off to war. The wife clings on to her husband and stares deeply into his eyes. He has a tough unreadable expression, as if he is telling his wife to be strong. Their young son tugs on both parents. On the right side of the background is their family home, and the left side is a troop of soldiers. The family stands perfectly in the middle of these two, suggesting the collision of public and private spheres the war will bring. The woman in this image stands outside her home, yet it is still visible, reflecting how women worked in a way that brought the domestic and public spheres together.

Wealthy plantation women took responsibility for taking care of their families, homes, and sometimes even their husbands’ businesses. Although their organizations did not achieve the large-scale popularity of their northern counterparts such as the USSC, southern women organized to help the Confederacy in similar ways and were especially successful as hospital matrons and nurses.

Southern plantation mistresses, “women in residence on plantations with 20 slaves or more”, held a confusing position within society. [7] They were of the powerful slaveholding class, yet were powerless against their husbands and society’s expectations for women.[8] Before the war, they were responsible for running their homes including their children and

sometimes enslaved laborers. These responsibilities intensified when men went to war. For example, when Elizabeth Thorn’s husband enlisted, Thorn kept all her domestic duties, while maintaining her husband’s cemetery business and feeding soldiers. [9] Southern homes stood in the middle of the war, so women took responsibility for helping soldiers from their own side and protecting their children from invading opposing soldiers. In Adalbert Volck’s “Searching For Arms”, Union soldiers assault a Confederate home. The mother in this scene wraps her daughter in her arms and drapes a curtain over both of them, since they are wearing clothing unfit to be seen by unknown men. She both preserves her daughter’s innocence by covering her and protects her from potential harm.

Southern women also took on even more public responsibilities working in military hospitals and worked as both nurses and matrons, who, in addition to regular nursing duties, essentially took responsibility for the day-to-day operations of the hospitals. Matrons and nurses filled in the gaps, attending to tasks that male doctors could not afford the time to do. In addition to seeing to the physical care of the wounded, they also assisted with emotional recovery and fostered relationships with patients. Such duties reflect the perception that women are naturally more caring than men; however, the new acknowledgment that women’s skills were valuable beyond the home was important in women’s progression in the nursing industry.

Women, considered “natural nurses” because of their supposedly intrinsic motherly qualities, received formalized nurse training in significant numbers for the first time in history. [11] Eventually, about 20,000 women worked as nurses or hospital workers during the war.[12] Despite this evolution, female nurses still faced many obstacles including being called “old hags” by male doctors and as well as confronted other prejudices. After the war, the American Medical Association required that hospitals have training for nurses, indicating that women’s participation in the war as nurses informed the professionalization of nursing. Even though women’s work in the public sphere closely mirrored the types of work they traditionally performed in the household, it laid the groundwork for women’s progress in the formal labor force and participation in other realms of American public life.

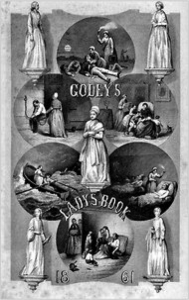

Referenced earlier in this paper, “The Sphere of Woman” from Godey’s Lady’s Book

epitomizes the antebellum vision of women as angels in the home. The cover of another issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book from 1861, just a year later, and the year the war began, strikes a much different tone. This image shows vignettes of women with depictions of other significant women, such as Florence Nightingale and Dorothea Dix[14], two prominent female nurses. Women perform tasks not just related to the home and children. They are shown caring for men, and active in dangerous situations in hospitals and even on a boat. Godey’s makes the shift of women’s roles in the Civil War evident through the change from its illustration of “The Sphere of Woman” to the later cover in which women take an active role in the public sphere. Despite the primarily domestic nature of their identities, women’s unprecedented foray into the public sphere during the Civil War had profound implications beyond the war. For example, because of their work in the USSC, women realized that they could enact change on the national level to give women’s work value. They advocated for better conditions and pay for other women through the New York Workingwomen’s Protective Union[15]. Many prominent women from USSC also became leaders of national organizations such as the American Women Suffrage Association and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.[16] Thus, women’s expanded roles during the Civil War laid the groundwork for their evolution of roles far beyond it.

[1] Women and the Law: Leaders, Cases, and Documents By Ashlyn K. Kuersten 16

[2] Robertson, Elizabeth. “The Union’s “Other Army”: The Women of the United States Sanitary Commission.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History (n.d.). 2.

[3] Robertson, Elizabeth. “The Union’s “Other Army”. 4.

[4] Robertson. “The Union’s ‘Other Army’”. 6.

[5] The idea that women should be “domestic, innocent, and utterly helpless”. “The Angel in the House.” Victorian Poetry, Poetics and Contexts. Accessed April 09, 2015. https://victorianpoetrypoeticsandcontext.wikispaces.com/The+Angel+in+the+House.

[6] Bensen, Virginia R. “The Women of Winchester, Virginia.” Emerging Civil War. November 30, 2011. Accessed April 09, 2015. http://emergingcivilwar.com/2011/11/30/the-women-of-winchester-virginia/.

[7] Clinton, Catherine. “Hidden Lives.” Preface to The Plantation Mistress: Woman’s World in the Old South, Xiii. New York: Pantheon Books, 1982.

[8] Wayne, Tiffany K. Women’s Roles in Nineteenth-century America. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007. 135.

[9] Wayne. “Women’s Roles in Nineteenth-century America”. 138

[10] Hilde, Libra Rose. Worth a Dozen Men: Women and Nursing in the Civil War South. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012. 46.

[11] Robertson 3

[12] Robertson 13

[13] Robertson 10

[14] Robertson 13

[15] Robertson 13

[16] Robertson 13

I found your essay to be very interesting. Although you’re writing about the Civil War era, I can’t help but mention the fact that the sentiments toward working women at that time are very similar to present day. At a time when they would have desperately needed to rely on the help of women, one would think men wouldn’t be so outwardly disapproving. of working women.I think connection to present day is what makes your essay both relevant and important.

You argue your topic convincingly, and the choice of images offers good support.

Very informative essay! I really like your analysis of Homer’s “Our Women in the War” – it really highlighted women’s roles during the war and the importance of women in hospitals, but also drew out the idea that images like these lessened the individual contributions of women. That being said, having portraits of women like Velazquez allows for those amazing individual stories to be told.

Caylie, I really enjoy how your essay uses an analyses of images from visual popular culture to consider the role of everyday women in the war effort and the lasting ramifications of their participation. I also appreciated your nuanced thesis–observing a potentially progressive change while also attending to the limits placed upon that progress. Your should be very proud of your work!