Elizabeth Leavitt

A portrait of Winnie Davis, daughter of the Confederate president Jefferson Davis, reigns from on high, given a privileged position at the Confederate Memorial Hall in New Orleans and showing Davis in her full splendor as a Mardi Gras queen of Comus. The theme of the 1892 parade was “Nippon, Land of the Rising Sun,” and Davis wears a white satin kimono with embroidered flowers on the sleeves, representing both the theme of the parade and the tradition of white dresses worn by Mardi Gras queens. Davis also wears an elaborate set of Comus jewels that are displayed alongside her portrait at New Orleans Confederate Memorial Hall. The jewels also fit in with the theme of “Nippon, Land of the Rising Sun”, in particular the scepter Davis holds delicately in her lap, has golden rays shooting out from the central stones at the bottom and the top of the scepter, evoking the idea of the sun. Davis also wears an ornate diamond necklace and a belt made of red gemstones and diamonds.

Though she wears a kimono and carries all the accoutrements of a far-eastern queen, Winnie Davis is still situated in the Mardi Gras queen tradition of New Orleans. Davis wears a white dress traditional of Mardi Gras queens and she sits in front of a plain brown background, a common mode for picturing women in antebellum period portraits.[1] The light source also hits Davis’s face, making her skin glow to an even whiter shade. Lastly, Davis holds her scepter delicately in her hands and looks demurely out at the viewer, with the grace of a true Southern Belle. The 1892 portrait of Winnie Davis establishes her rule simultaneously as the Princess of the Confederacy and the Queen of Comus.

123 years later, the photograph of the 2015 queen of the Rex Parade bears a striking similarity to the portrait of Winnie Davis though in this photograph the queen wears even more royal regalia including a crown, a long fur-lined train, and an elaborate gold dress, which perhaps indicates an increasing desire to appear as royalty. Susan Langenhennig’s 2012 article in The Times-Picayune, “Designing Carnival’s queen gowns takes a couturier’s eye and an aptitude for engineering”, discusses the extensive amount of labor and money that goes into making Mardi Gras queen gowns such as the one the 2015 Queen of Rex wears. The weight of the dress itself usually weighs up to 100 pounds, takes about six to ten months to construct, and has a price tag between $6000 and $12,000.[2] The amount of time and money spent on these elaborate dresses clearly illustrates the importance of elevating the Mardi Gras queen to the level of royalty.

To most, Mardi Gras often conjures images of massive celebrations and evokes the idea of a giant party that takes place throughout New Orleans. Almost the entire city of New Orleans is somehow involved in Mardi Gras, and the celebration has become a major tourist attraction with a huge economic impact on the city. But many of the visitors and even many of the city’s residents fail to realize the existence of a much darker side of Mardi Gras that stretches all the way back to its beginnings after the Civil War. The Portrait of Winnie Davis as Queen of Comus illustrates Mardi Gras’ deep roots in the Civil War and the photograph of the 2015 Queen of Rex, depicts the continuing tradition of elevating Southern belles to the level of royalty. The symbol of the Southern Belle acts as one of the central to the traditions of Mardi Gras and her deep ties to the idea of the “Old South” has become a way to reinforce social and racial divisions in New Orleans. This essay will argue that at the heart of Mardi Gras is the desire to fortify racial, social, and gender hierarchies through various constructs of power formulated by the elite white men of New Orleans, and their use of Mardi Gras queens as a critical way of legitimizing their power.

The Racialized Roots of Mardi Gras in New Orleans

Though it looks much different now, the tradition of Mardi Gras goes back to the French colonial period in Louisiana, and the Mistick Krewe of Comus became the first permanent Mardi Gras organization in 1857, just a few years before the start of the Civil War.[3] The myth of the creation of the Krewe of Comus tells of how “the quaint French observance of the day before Lent had fallen into the hands of drunken masqueraders, uncouth sailors, and hoodlums,” but a group of prominent citizens “rushed to the rescue” and formed Comus as a permanent organization in order to reshape the traditions of Mardi Gras.[4] Comus organized processions through the streets and then held a ball for invited guests until the Civil War brought a brief interruption to the celebrations. After the Civil War, the old Krewes reintroduced Mardi Gras and more krewes were formed. As Karen Leathem observes, the tradition of krewes dressing like royalty began after the Civil War as a way of enshrining white power:

In the decades following 1870, the elite organizations dramatized the parallel hierarchies of white supremacy and patriarchy through elaborate parades and dazzling balls. Anxious about their position during Louisiana’s turbulent reconstruction and afterward, bank presidents, cotton merchants, and lumber barons asserted their power as carnival kings, while their debutante daughters embodied the ideals of southern womanhood as carnival queens.[5]

These Mardi Gras traditions reified the myth of southern nobility and reinforced white supremacy, helping the elite white men of New Orleans maintain political, social, and economic control over the city.

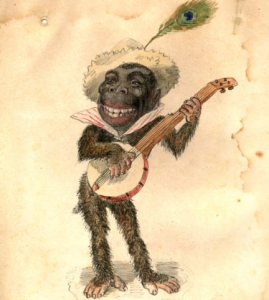

Early parade themes reflect the political and social discord in Louisiana and the desire for the white elite to continue to assert their dominance. In 1873 the parade theme of Comus was “Missing Links to Darwin’s Origin of Species,” and the costumes and floats were designed to stir up opposition to the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments, which gave African Americans the protection of their rights under the law and the ability to vote.[6] The costume designs for this parade, most notably the watercolor sketch for a gorilla costume, indicate the desire to associate black men with primitive animals. This image depicts an anthropomorphized gorilla standing on two legs as it plays a banjo. The figure’s exaggerated simian features—the thick, dark hair all over its body, as well as hands and feet with opposable thumbs—reinforce its connection to the primate family while its humanized facial features include exaggerated physiognomy meant to conjure period caricatures of black men. Wide, flared nostrils and big ears accent the face while large, full lips painted red frame an outsized, white-toothed smile. The figure’s clothing and accessories—a straw hat with a single peacock feather sticking out from the top and pink and white striped collar that recall minstrel images—also place it in the liminal space between human and animal to which Southern Redeemers wanted to assign black men, furthering the political agenda of the elite white males of Comus.

The “Missing Links” parade and the gorilla costume in particular, were later reviewed by the Daily Picayune, noting the distinct resonance the costume had with certain parts of the New Orleans population. The author of the article compares the gorilla costume to “the broader-mouthed varieties of our own citizens, so Ethiopian in his exuberant glee,” essentially pointing out the parallels between the physiognomy of the gorilla and black men, if these parallels were not already obvious to the reader.[7] Images like the Comus gorilla costume were designed to symbolically remove the threat of black masculinity that conservative newspapers in the Reconstruction era had magnified, in particular, the threat of black men towards white women.[8] The threat of black masculinity created a strong rhetoric for elite white men who sought the suppression of African American rights as a means of protecting white women and in many parts of the South, justified a multitude of lynchings.[9] Thus, the gorilla costumed figure exoticised this perceived threat in the minds of all who saw it during the Comus parade; the idea that the silly-looking, primitive, banjo-playing gorilla would ever be a threat to a Southern Belle, like Mardi Gras Queen Winnie Davis, would have seemed impossible.

Mardi Gras costumes and parade themes have continued to be a way for the elite men of New Orleans to assert their rule over the city. In 1992, the same year New Orleans passed an ordinance desegregating Mardi Gras krewes, the theme of the Rex parade was “Voyages of Discovery,” which essentially retold the story of the discovery and colonization of America from the perspective of a white man. Barbara Vennman describes an account of one float from the Rex parade that depicted a particularly narrow view of history from the lens of “white male power through a full-body figure of Christopher Columbus standing closely behind a cannon, suggesting its extension from his body as an erect phallus.”[10] The glorification of figures like Christopher Columbus and images of other white male historical figures with dubious histories during Mardi Gras parades reinforces the narrative of the white male patriarch as the ruling elite. The massive phallic imagery also reinforces the gender hierarchy within the New Orleans elite, demonstrating not only their physical power over women, but their authoritative role both historically and in the present day, making this float symbolic of both white and male power.

Gendering Carnival: Mardi Gras Queens; A Particular Brand of Southern Belle

The Mardi Gras tradition reinforces the ruling white patriarchy both in terms of race and wealth, but also in terms of gender, through the practice of choosing Mardi Gras queens. The members of the Mardi Gras krewes choose the queen from a selection of young debutantes, usually as a way of honoring the girl’s father or grandfather, who are members of the same krewe. Temple Browne Jr., the king of Rex in 1992, discusses the importance of the tradition of Mardi Gras queens, relating them directly Southern Belles and asserting that the process is not a demeaning one: “We honor them…we put them on a very lovely pedestal. And I do believe in Southern belles. Not Scarlett O’Haras. I don’t mean that. But I believe in femininity. God made us different.”[11] Browne’s idea of a Mardi Gras queen as an exalted Southern Belle, a symbol whose white elite femininity reinforces social hierarchies, but also a symbol who holds no real independent power and operates only through the agency of men.

John Teunisson, Hermes Mardi Gras Court, circa 1901-1920

As a Southern Belle elevated to the level of royalty, the Mardi Gras queen represents the epitome of Southern white femininity. John Teunisson’s photograph of the Hermes Mardi Gras Court from the early 1900s features the Mardi Gras krewe’s queen arrayed in all her royal regalia. Flanked on either side by three of her maids and two young male pages. She and her court stand atop a slightly elevated stage, her ornately embroidered white dress finishing in a long train that cascades down the steps into the foreground of the image. Behind them, an enormous painting surrounded by an ornate frame festooned by two large satin drapes showcases a knight brandishing his sword on the back of a dragon, reminding the room that men are the ones controlling power, perhaps even alluding to the knights of the Ku Klux Klan. On either side of the painting, two raised candelabras contain dozens of candles, illuminating the room with a warm glow. The combined effect of all of these elements makes the room itself feel like the throne room of an imaginary castle, giving the viewer a glimpse into the imagined world of white Southern royalty.

The notion of the Southern Belle grew out of the need for a central figure representing the Old South during the Civil War, Reconstruction, and even throughout the 20th century. In Reconstructing Dixie, Tara McPherson discusses the need for a figure to represent the South and how it was “the southern lady as a central player in the aggrandizement of Dixie, a figure who, along with her younger counterpart, the belle, served as a linchpin of nineteenth century revisionist versions of the Old South”.[12] Therefore, the Southern Belle helped redefine the hierarchy of the post-Civil War divided society and embodied the ideals of the white, southern elite. Though the Belle was a symbol for the traditions of the Old South in general, New Orleans fashioned its own particular iteration of Southern Belle – the Mardi Gras queen. The Mardi Gras queen developed out of the early krewes of elite white men who sought to redefine social hierarchy by dressing like royalty and asserted their power through exclusivity, while “their debutante daughters embodied the ideals of southern womanhood as carnival queens.”[13] Essentially, the Mardi Gras queen holds no power in her own right, but acts as a symbolic figure representing the power of elite white men.

A 1930s photograph of a Mardi Gras ball in New Orleans reveals the tradition of the male krewe members remaining masked throughout the evening while enjoying their unmasked female guests, a practice that allowed them to “retain their authority as masters of the gaze in their objectification of unmasked debutantes, wives and female guests.”[14]. In the large ballroom teeming with guests, non-krewe members wait on the side of the dance floor and look on as the krewe members and their dates share the first dance. The women wear floor-length ball gowns, while the still-masked krewe members remain in their costumes from the parade procession. This ritual of krewe members remaining masked during balls, as well as the tradition of choosing a Mardi Gras queen, adds another level to the power structure created by the krewe members of Mardi Gras. Through Mardi Gras, the white male elite asserted its dominance using the racial and social exclusivity of krewe membership as well as establishing their dominant gender roles through traditions of masking and selecting Mardi Gras queens.

Purple, Gold, Green, and Black: African American Mardi Gras Krewes and Their Queens

In a complicated response to the exclusive membership practices and the male-dominant traditions of krewes like Comus and Momus, the first all-black Mardi Gras krewes began to appear in the early 1900s.[15] The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club crowned its first King in 1909 as a way of parodying the traditions of Rex, and the Zulu krewe designed their parade to make fun of stereotypical images of African Americans through appropriating and redeploying those types. The photograph, The Zulu King debarks on the morning of Mardi Gras in his tug boat at the head of the New Basin Canal in 1936, shows the king and various other krewe members wearing black face on top of white face, an arguably subversive practice the krewe adopted as a means of poking fun at white actors in minstrel shows and their own performance of blackness. Zulu krewe members also adopted a regular roster of stereotypically “black characters” such as the witch doctors, ambassador, mayor, province prince, governor and soulful warriors who appeared every year in the parade.[16] The minstrel-inspired parody performed by the Zulu krewe every year during Mardi Gras acted as a way of acknowledging much of the city’s African heritage, while also demanding a certain recognition from the city’s other Mardi Gras krewes and bridging the gap between black and white carnival traditions, most notably with the male-dominant tradition of selecting a Mardi Gras queen.[17]

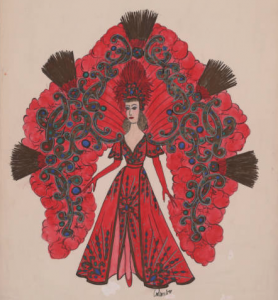

Zulu and other black Mardi Gras krewes continued the use of patriarchal rituals such as choosing Mardi Gras queens as way of keeping up with the long-standing traditions of Mardi Gras as well as defining gender roles within elite black society. For the early history of Zulu, male krewe members of Zulu cross-dressed as elaborately costumed queens; this continued until 1933[18] when the krewe members chose Mardi Gras queens from a selection of the daughters and granddaughters of other krewe members as a way to honor their male relatives.[19] The 1997 Zulu queen costume design demonstrates the desire for the queen to appear as an opulent spectacle. The queen’s dress and headdress shine in various shades of red and intricate beadwork designs cover the floor-length gown. The queen also wears an elaborate collar and headdress that would have most likely been made from feathers as well as headpiece that depicts the letter “Z”. Though designed specifically for a black woman, the woman in the costume design has pale white skin, potentially revealing the desire for the queen to be a light-skinned woman or suggesting that she fills a role quite similar to her white counterparts. The figure also has small and dainty hands and feet ostensibly giving her a look much closer to prototypical white Southern Belle and therefore of traditional Mardi Gras queens. The similarity in costume design between the Zulu queen and the costumes worn by the queens of parades like Rex and Comus, reflects the notion that queens of Mardi Gras, regardless of race, must exemplify a particular gendered ideal.

Although many of the early African American Mardi Gras krewes followed similar male-dominant practices to the white Mardi Gras krewes, small groups of African American women began to rebel against the patriarchal traditions of Mardi Gras in the early 1900s. In 1912, a group of prostitutes from the Storyville district of New Orleans, formed their own Mardi Gras krewe, the Baby Dolls.[20] Unburdened by the desire be part of respectable society and rebelling against Victorian restrictions on sexuality, the Baby Dolls dressed in short skirts, smoked cigars, and threw money at men while parading in the streets during Mardi Gras.[21] The Baby Dolls and their practice of gender role reversal soon became an expected part of Mardi Gras, and they would join the tail end of the Zulu.[22] The 1942 photograph of the Baby Dolls depicts them dressed in their customary short dresses and carrying traditionally male objects, such as canes.

Today, the Baby Dolls continue to march in the streets during Mardi Gras as a way of carrying on their predecessors’ traditions and asserting their place both as women and African Americans in the New Orleans community. Although female krewes such as the Baby Dolls have worked to redefine gender roles during Mardi Gras, for older krewes like Zulu, little has changed about women’s roles. Despite creating a unique racialized aesthetic for its male krewe members, Zulu has yet to develop a distinct tradition for its female participants, especially their Mardi Gras queens. The 2014 photograph of the Zulu King and Queen demonstrates the remarkable similarities between the Zulu Queen and the 2015 Queen of Rex and Winnie Davis as Queen of Comus in 1892. The Zulu Queen wears the traditional white dress worn by Mardi Gras queens, white gloves, a sparkling tiara, and holds an ornate scepter, all conventional imagery used by the elite white krewes to symbolize the queen’s position as ruler of Mardi Gras and as an ideal Southern Belle. The Zulu queen, then, functions as another constructed male symbol, in this case she becomes part of the male-dominant framework of Mardi Gras krewes, likely as a way for the black men of Zulu to legitimize their krewe in relation to the old elite white krewes that dominate Mardi Gras.

Confronting the Past: Contemporary Responses to Mardi Gras Traditions

Today, contemporary artists like Carrie Mae Weems have begun to explore some of the many Mardi Gras traditions rooted in the post-Civil War fallout. In several elements of her installation, The Louisiana Project, Weems explores the legacy of antebellum race and gender dynamics, including those specifically related to Mardi Gras. In a powerful photograph entitled Missing Link: Despair, Weems tackles the racism tied to early costume designs such as Gorilla from the 1873 “Missing Links” Comus parade. In the photograph, Weems, dressed in a suit wearing the gorilla mask, hides both her racial and sexual identity, highlighting the traditions of masking that take place during Mardi Gras. Though her costume alludes to the racist 1873 gorilla costume, Weems reverses both race and gender roles, by masking her identity as an African American woman and asserting the idea that she could be anyone under her costume.

In Missing Link: Despair, Weems wears an all-black suit that comprises of long pants, a tuxedo jacket, and a turtleneck that meets the bottom of her mask. On top of the gorilla mask, she dons a black top-hat, recalling the peacock feather in the straw hat of Briton’s Gorilla costume design. The only shocks of color in the almost monotone image come from the white flower on Weems’ lapel and her glowing, white-gloved hands. The artist’s left hand, clenched in a fist at her side connotes power while her right hand covers her genitalia, as if to obscure the fact she is a woman. The placement of her right hand and its outstretched fingers, reminiscent of those of the banjo-strumming ape-like figure in the Comus Gorilla costume, also allude to the original 1873 image as does her contrapposto pose, similar to that of the gorilla swaying to the music.

Weems’ Missing Link: Despair clearly references the racist undertones in the Gorilla costume design from the Missing Links Parade, but Weems’ photograph asserts a new, more gendered component on top of the older image of the gorilla. The photograph now draws upon not only deep racial discrimination in the history of Mardi Gras, but also the subjugated status of black women. Weems’ use of masking to hide and create identity also calls to mind the similar rituals the elite white men of the old Mardi Gras krewes practice to assert their place as the kings of Mardi Gras in order to enshrine their place at the top of the social and racial hierarchy of New Orleans. Missing Links: Despair, plays on both the racial and gender discrimination fundamental to the hierarchy of Mardi Gras, but Weems turns the tradition of masking in on itself: it is now the black woman who can direct her gaze at anyone while hiding her identity behind a mask.

Elite white men have constructed many of the ongoing traditions of Mardi Gras that are both popular today and at the end of the Civil War. The desire to enshrine antebellum social systems drove, and continues to drive, many of the gendered and racialized traditions of Mardi Gras. The construction of the Mardi Gras queen legitimized the power of the elite white men of New Orleans, combining the figure of the Southern Belle with symbols of royalty, thus making her the figurehead for the fortification of antebellum social and racial hierarchies. The Southern Belle as a ruler of Mardi Gras managed to seep its way into the traditions of African American Mardi Gras krewes, when they too gave a Mardi Gras queen the symbolic power to rule over their parade. Though artists like Carrie Mae Weems try to deconstruct the very complicated history of Mardi Gras, the traditions of today are still very firmly rooted in the past.

Works Cited

Vennman, Barbara, “Boundary Face-Off: New Orleans Civil Rights Law and Carnival Tradition”, The Drama Review. Vol. 37, No.3 (Autumn, 1993). 76-109

Leathem, Karen Trahan, “A Carnival According to their own desires: Gender and Mardi Gras in New Orleans, 1870-1941”. 1994.

Smith, Felipe, “Things You’d Image Zulu Tribes to Do: The Zulu Parade in New Orleans”, African Arts. Summer 2013, Vol. 46, NO. 2. 2013.

Langenhennig, Susan, “Designing Carnival’s queen gowns takes a couturier’s eye and an aptitude for engineering,” The Times-Picayune. February 12, 2012. http://www.nola.com/fashion/index.ssf/2012/02/creating_carnival_queen_gowns.html

McPherson, Tara. Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Scott, Liz, “Queen Gee,” New Orleans Magazine. February 2000. 14-16

Gill, James, “The Krewes and the Klan,” Lords of Misrule: Mardi Gras and the Politics of Race in New Orleans. University Press of Mississippi 1997.

Censer, Jane Turner , “Women and the Old Plantation,” The Reconstruction of White Southern Womanhood 1865-1895, Louisiana State University Press. 2003.

Weems, Carrie Mae, “Carrie Mae Weems: Biography,” http://carriemaeweems.net/bio.html

Abrams, Eve, “Baby Dolls Assert Their Place by Parading in the Streets,” 89.9 WWNO The University of New Orleans. Wednesday, February 4, 2015. http://wwno.org/post/baby-dolls-assert-their-place-parading-streets#.VNJ_x-d6yGA.facebook

Vaz, Kim, “’They call me Baby Doll’: Resurrection of a Mardi Gras Tradition,” Louisiana Cultural Vistas, Winter 2010-2011.

[1] “Portraiture, Landscapes, and Marine Scenes in Nineteenth-Century Louisiana,” Collecting Passions: Highlights from the LSU Museum of Art Collection

[2] Susan Langenhennig, “Designing Carnival’s queen gowns takes a couturier’s eye and an aptitude for engineering,” The Times-Picayune. February 12, 2012. http://www.nola.com/fashion/index.ssf/2012/02/creating_carnival_queen_gowns.html

[3] Karen Leathem, “A Carnival According to their own desires: Gender and Mardi Gras in New Orleans, 1870-1941”. 1994. 1

[4] Leathem, “A Carnival According to their own desires”. 1

[5] Leathem, “A Carnival According to their own desires”. 3

[6] Barabara Vennman, “Boundary Face-Off: New Orleans Civil Rights Law and Carnival Tradition”, The Drama Review. Vol. 37, No.3. 77

[7] James Gill, “The Krewes and the Klan,” Lords of Misrule: Mardi Gras and the Politics of Race in New Orleans. University Press of Mississippi 1997. 104

[8] Jane Turner Censer, “Women and the Old Plantation,” The Reconstruction of White Southern Womanhood 1865-1895, Louisiana State University Press. 2003. 144

[9] Censer, “Women and the Old Plantation”.148

[10] Vennman, “Boundary Face-Off: New Orleans Civil Rights Law and Carnival Tradition”. 76

[11] Vennman, “Boundary Face-Off: New Orleans Civil Rights Law and Carnival Tradition”. 81

[12] Tara McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender and Nostalgia in the Imagined South. 2003. 19

[13] Leathem, A Carnival According to Their Own Desires, iii

[14] Vennman, “Boundary Face-Off: New Orleans Civil Rights Law and Carnival Tradition”. 81

[15] Vennman, “Boundary Face-Off: New Orleans Civil Rights Law and Carnival Tradition”. 85

[16] Vennman, “Boundary Face-Off: New Orleans Civil Rights Law and Carnival Tradition”. 85

[17] Felipe Smith, “Things You’d Imagine Zulu Tribes to Do: The Zulu Parade in New Orleans,” African Arts. Summer 2013. 27

[18] Liz Scott, “Queen Gee,” New Orleans Magazine. February 2000. 15

[19] Vennman, “Boundary Face-Off: New Orleans Civil Rights Law and Carnival Tradition”. 85

[20] Eve Abrams, “Baby Dolls Assert Their Place by Parading in the Streets,” 89.9 WWNO The University of New Orleans. Wednesday, February 4, 2015.

[21] Abrams, “Baby Dolls Assert Their Place by Parading in the Streets”. and Kim Vaz, “’They call me Baby Doll’: Resurrection of a Mardi Gras Tradition,” Louisiana Cultural Vistas. Winter 2010-2011. 89

[22] Vaz, “’They call me Baby Doll’: Resurrection of a Mardi Gras Tradition”. 88

Elizabeth, I love your essay! Prior to reading this I had been one of those people who just thought of Mardi Gras as a giant party. I had known about the darker side of Mardi Gras, but not to this extent. The images that you chose definitely help string together and strengthen your argument, they’re also very intriguing (the missing link: despair).

Elizabeth, I really appreciate the way in which your essay brings the concerns of the exhibition from the Civil War era into the present day and the way in which you use images–from the Missing Link costume to Carrie Mae Weems’s photograph–to accomplish this. I also really enjoyed your central argument about the Mardi Gras Queen as a local iteration of the Southern Belle that elevated the Belle’s status to one of royalty. You started with a strong first draft and continued to refine it to produce a polished finished product. You should be proud of your accomplishment.

Elizabeth, I love your essay!. I had known about the darker side of Mardi Gras, but not to this extent.