Sarah Monaco

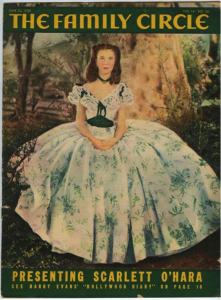

A photograph of the opening scene from Gone With the Wind, sold as part of a color set around the time of the film’s 1939 premier, shows Scarlett as the archetypal Southern belle (fig. 1).[1] For generations of Americans who grew up with Gone With the Wind, the idea of the Southern belle is inextricable from this and other images of Scarlett’s big dresses, verdant plantation, and coquettish charm. In the image, Scarlett stands against the classic background of rolling green hills and the beautiful plantation Tara. That Tara appears in the background and that Scarlett appears small in the wide landscape increases the impression of the plantation’s vastness. Furthermore, Scarlett’s dress, its many layers spread over an enormous hoop skirt, displays her wealth, a staple of the Southern belle. The many acres of Tara and estates like it are Scarlett’s whole world. In this image, one might imagine that she could run and run without ever reaching the property’s boundary. A belle’s charm always draws lots of suitors, and we see two brothers on the porch, each begging for Scarlett’s attention. Mammy, who assumes most motherly duties and raises the belle, is an integral part of the Southern belle’s world. Here, we see her calling out after Scarlett, clearly keeping her young charge under a watchful eye.

Scarlett is an integral part of Gone With the Wind’s romanticized notion of the antebellum plantation; she is a culmination of their anxieties and ideals, an embodiment of their values and morals. The iconic image of Scarlett and Tara embodies what it means to be a Southern belle. While there were certainly graceful and gracious women who lived on plantations in the antebellum South, the Southern belle as we know her is a post-bellum cultural fiction propagated by writers and filmmakers in the decades after the Civil War and even into the present day. The image of the belle later became a cultural icon successfully deployed in advertising campaigns. This paper will argue that the commercialization of the Southern belle achieved success by exploiting Old South mythology and the attributes of the Southern belle.

Historians have put forth two compelling theories about the origins of the romanticized South: the Industrial Revolution and reunion between the Union and the former Confederate states. The Industrial Revolution, the South felt, brought threats such as materialism, greed, poverty, and prostitution, all of which directly undermine human morality.[2] Scholars have suggested that Southern society reacted to these anxieties in the same way that the Victorians had; by idealizing women and the home in the face of moral chaos.[3] However, the South added a sense of moral superiority over the North, who they felt embraced immortality along with industrialization. Southern plantation life was also founded upon a belief that agriculture was a more honest means of earning a living, a contrast to the factory-filled North.[4] This approach gave rise to the believed Southern moral superiority over the North.[5] It was under this belief system that the Southern belle was created for plantation life, but not the demands of modern life. Thus Southerners, in the decades after the Civil War, constructed an idealized woman: a virtuous belle with a delicate nature who need not work at all.[6]

The status of race seemed similarly in flux in the decades after the Civil War.[7] Thus, the Southern belle became an object to protect, not only from the evils of the Industrial Revolution, but also from formerly enslaved men. G. W. Griffith’s 1915 film Birth of a Nation, the nation’s first blockbuster film, represents the South’s fears about racial integration during and after the Civil War.[8] Importantly, it frames Southern femininity as endangered by ‘aggressive’ black men. A film still Flora and Gus captures this racial anxiety and tension and shows the presumed stakes of protecting a belle’s honor (fig. 2). In this scene, Union solider Gus proposes to Flora who wears a light, ruffled dress, looking like the typical belle. Gus, in contrast to Flora, is extremely dark and wild-eyed; his posture is aggressive, suggestive of his threat to Flora. As the proposal is met with a dissatisfying response, Gus begins to chase Flora, and she commits suicide by leaping to her death. Rather than graciously accepting this rejection like a civilized person, Gus regresses to a primal state. Scenes like this allude to the aggressive black masculinity that was perceived as a threat to white femininity.[9] Thus, Flora’s suicide is morally justified by the threat of unwelcome racial mixing that the marriage proposal implies. For a society with increasing racial instability, the protection of the innocent white woman from racial threat provided an excuse to maintain a strict racial hierarchy.

The second theory of the South’s romanticization cites an attempt at reunion and reconciliation between the North and the South. After the Civil War was over, the United States faced the choice between Northern and Southern reunion or justice for the newly emancipated slaves.[10] For contemporaries, it seemed as though one could not be had without the other. The attractive Old South myth—an intrinsic part of the ideology of the Lost Cause—serves to reunite the country under an idealized past rather than give it justice. The romanticized version of the South glosses over the harsh realities of slavery and emphasizes the fairytale of the belle.[11] The Old South myth also functions to parallel the South’s believed moral struggle of the Civil War with the moral struggles of the Southern belle.[12] Due to the belle’s high moral standards, the belle faced moral threats daily; preserving her purity and social reputation were constant burdens. As the embodiment of strong character and virtue, the belle’s moral struggles symbolize the moral battles that the South felt they faced in fighting the war against the North, reinforcing the Southern sense of moral superiority. Whatever the motivations, the Southern belle emerged in the postwar South as the model of purity and charm, comfortably part of a romanticized, idealized notion of the antebellum South.

In another image from Gone With the Wind, a scene of Scarlett at a plantation barbecue, reveals the gender relationships of the Old South as they were idealized after the War (fig. 3). In the middle of the composition, Scarlett is literally the center of attention, to both the viewer and the men that surround her.Her charm and wit lure in every man at the barbecue, a quintessential part of the Southern belle’s persona. A woman in the nineteenth century lacked power amongst men. While the presumed innocence and fragility of the Southern belle puts her on a pedestal, it also subjugates her.[13] Her charm and wit lure in every man at the barbecue, a quintessential part of the Southern belle’s persona. A woman in the nineteenth century lacked power amongst men. While the presumed innocence and fragility of the Southern belle puts her on a pedestal, it also subjugates her.[13] The pre-Civil War woman was powerless to protect herself against constant racial threat and, thus, was at the mercy of Southern white men. The trope also reinforces paternalistic gender roles, where men were expected to gallantly protect a woman’s purity.[14] Through manipulation, the Southern female could correct the power inequality between men and women, but under the socially acceptable guise of charm.[15] This attribute allowed women to work within the constructed gender roles of the Old South.

Despite Scarlett’s status as the iconic Southern belle, some scholars suggest that she is no such thing, for she deviates from the path of prescribed gender roles and is of Irish descent.[16] Malcolm Cowley argues that although the target of the Old South’s racism was first and foremost African Americans, no ethnicity aside from English was safe from racial stigma. Second, Cowley suggests Scarlett, at the end of the film, assumes a male gender role by doing such things as running the lumber mill. Images like the film still of Scarlett after the War encapsulates the scholars’ objections and exemplify her shift from belle to modern woman. Scarlett is literally and metaphorically surrounded by the ruin of the War and industrialization (fig.4).Here, we no longer see Scarlett in the innocent, girlish colors from before, but a vivid red velvet dress. The velvet red dress alludes to Scarlett’s shift from belle to a modern woman; she is now married and thrives in the post-Civil War world. Similarly, the velvet functions as a reminder that the modern Scarlett is independent. Scarlett emerges from the war as a new woman, one that does not need to follow constructed gender roles to be successful, as we see here. Scarlett’s stern expression reflects the shift in her personality over the course of the film. Earlier, we saw Scarlett’s frivolous and naïve attitude. After the war, Scarlett is a completely different woman; Scarlett is more serious, now a businesswoman running the lumberyard. The room is a stark contrast to Scarlett; the sofa is frayed, the walls are covered in dirt, and the wooden structure outside is in shambles. While Scarlett is able to adapt and move forward after the war, the room serves as a reminder that the scars of the war are still far from gone. Yet despite stepping outside of these carefully constructed gender norms, Scarlett has endured in pop culture as the prototypical Southern belle.

Three years after the movie premier of Gone With the Wind, several cosmetic companies saw the belle as something to capitalize on, selling the fantasy of the Old South with the use of their product. Avon’s advertisement from a 1942 issue of Cosmopolitan sells more than just makeup and perfume, they sell the promise that all the romance of Gone With the Wind will be yours with the use of their products (fig. 5). The image makes an unapologetic allusion to Gone With the Wind in several ways. The silhouette of old oak trees and rolling hills frame a plantation home, a staple of Old South imagery. The plantation intentionally resembles the iconic home Tara. Avon alludes to Tara in order to insinuate that, if you use their products, you will be transported to the Old South, made a dreamland by popular culture. Similarly, the illustrator renders the young woman in the advertisement in a dress that recalls Scarlett O’Hara. The woman in the advertisement wears the same type of dress as the one that Scarlett wears in the opening scenes of Gone With the Wind – a dress reproduced in many images, including the cover of Family Circle Magazine (fig. 6). The cosmetics company, then,capitalizes on the popularity of the film and book to promote their products. By using a popular culture reference, Avon associates the use of their product with icons, such as Scarlett O’Hara.

The belle’s floral dress references her purity, articulating the traits of the stereotypical Southern belle. This generic woman becomes part of the natural scenery in her floral-print dress; the artist even renders a lily-white magnolia around her waist. This reference to flowers has a duel meaning. First, it allows the woman to embody the summer fragrance of the perfumes and cosmetic products, as though all of her freshness and daintiness has been captured into a single bottle of Avon fragrance. Yet, flowers are also a symbol of the belle’s purity. Thus, if you buy Avon’s products, you will become a Southern belle, the pinnacle of innocence and purity, and attain the fantasy lifestyle that the advertisement promises. This sales pitch, however, depends on the established trope of the Southern belle as the flower of the South.

Of course, Avon conveniently omits one inescapable component of plantations: slaves. Plantations depended on enslaved labor for their economic success, yet, in the Avon image, slaves are nowhere in sight. Without depicting the reality of enslaved workers, the scene becomes a sanitized version of the Old South, erasing any unpleasant reminders of the institution of slavery and preserving the image of the romanticized Old South lifestyle that Avon so fervently sells.

Another cosmetic company similarly sells a Southern dreamworld. Instead of Scarlett, though, Old South Beauty Products appropriates the Cinderella tale, transplanting the belle into the fantasy of an antebellum romance between a charming soldier and his belle (fig. 7).The handsome soldier wears his military formals, signifying his courage and achievement as a soldier, and greets his belle, whose fairytale dress sparkles in the forefront of the advertisement. The soldier becomes ‘Prince Charming,’ complete with a horse-drawn carriage waiting behind them, and it would be no surprise to see a glass slipper under Cinderella’s dress. The cosmetics company, thus, likens the use of its products with a fairytale ending, even stating a “romance that lives forever” in describing their product, a paraphrasing of ‘happily ever after.’

Nevertheless, the scene is distinctly Southern. The fairytale ending takes place on the porch of a plantation, with the iconic wraparound porch stretching out of the frame. The silhouette of an oak tree gestures the consumer’s gaze toward a steamboat, chugging along the Mississippi River. The Mississippi connected the country by boat, and thus, moved crops and other goods that were used to support the Southern economy. The steamboat in the background becomes a reminder of Southern commerce and its vast reach. However, like the Avon advertisement, the fruits of slavery are rendered, but the enslaved laborers who produced them are not, utilizing the romanticized version of the South to sell cosmetics to the general public.

The ease with which Cinderella can be transplanted into the antebellum South reveals just how constructed these worlds are. Cinderella, a fabled Princess, is an easy fit with the constructed world of the romanticized South; the combination is seamless. The Old South logo shows the company’s origins in New York, thus proving that the entire country bought into this fabricated version of the Old South. The fact that the Old South could be constructed and contorted to appeal to the general population as part of a popular sales pitch speaks to how warped the fantasy of the antebellum South became; tourist destinations like Oak Alley plantation continue to promote the fantasy today.

People still buy the Old South today because of its vast popularity and timeless charm. The Southern belle is the most important component of the Old South’s enduring appeal. The constant racial threat to the belle and her emphasis on morality made the belle a popular trope in the post-Civil War South. Once the belle was fully commercialized and popularized by the film Gone With the Wind, her visual representation was used to advertise products, such as cosmetics. Even today we see the iconic Southern belle sold through paper dolls, Barbie dolls, and films like Steel Magnolias. Madame Alexander , a collectible doll company, sells the Old South through their Gone With the Wind collection (fig. 8). Scarlett is still sold in her costume from the scene of Scarlett and Tara, one of her most memorable outfits and one that identifies her as the quintessential belle. Thus, the Old South remains very much alive through the mythology, commercialization, and everlasting appeal.

[1] An advertisement for the image appears in the original press book, the publicity aid sent to exhibitors and theater owners at the film’s release. Slight differences in the position of the peacocks and the young men on the porch signal this is not a film still, but rather a posed photograph. “Gone With the Wind,” press book, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939): 15.

[2] Seidel, The Southern Belle in the American Novel.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 169.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Cullen, Race and Reunion book review.

[9] Welter, The Cult of True Womanhood, 151-174.

[10] Cullen, Race and Reunion book review.

[11] Wetta and Novelli, The Long Reconstruction, 129-142.

[12] Farnham, The Education of the Southern Belle, 186.

[13] Welter, The Cult of True Womanhood, 151-174.

[14] Farnham, The Education of the Southern Belle, 181.

[15] Ibid., 186.

[16] McGraw, Scarlett O’Hara and Ethnic Identity.

Works Cited

Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860,” American Quarterly (1966): 151-174.

Christie Anne Farnham, The Education of the Southern Belle (New York: NYU Press, 1994), 181-186.

Eliza Russi Lowen McGraw, “Scarlett O’Hara and Ethnic Identity,” review of Southern Belle With Her Irish Up, by Malcolm Cowley. The South Atlantic Review, Winter 2000, http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.tulane.edu:2048/stable/3201928?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

Frank J. Wetta and Martin A. Novelli, The Long Reconstruction: The Post-Civil War South in History, Film, and Memory (New York: Routledge, 2014), 129-142.

Jim Allen, review of Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, by David W. Blight. The Historical Review, February 2002, http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.tulane.edu:2048/stable/10.1086/532156?seq=0#abstract.

Kathryn L. Cox, Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture (UNC Press, 2011).

Kathryn Lee Seidel, The Southern Belle in the American Novel (Tampa: USF Press, 1985).

Lynette Boney Wrenn, Cinderella of the New South: A History of the Cottonseed Industry, 1855-1955 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1995), xvi-xxiv.

You used some very telling images and made me see the Southern Belle in a completely different light by encouraging me to really think about what she represents. The Belle has become this idealized icon that is essentially a myth. The way you connect this myth with the idealization of the Old South is very compelling. You forced me to make the realization that the perpetuation of the Southern Belle as an icon also perpetuates the ideals of the Old South.

I think that your use of Scarlett O’Hara as the epitome of a Southern belle makes your argument clear and very strong. I think its also very important that you discussed how the war transformed her into a more modern woman. I’m glad you touched on the parts that depictions of the belle leave out, just like most plantation tours omit talking about who really built them and focus on the beautiful and romantic aspects.

Sarah, your essay represents a lot of dedication and hard work, particularly in terms of paring down the many ideas that were in your original draft to a manageable topic that could be supported with visual and historical evidence. I really like the angle with which you chose to approach the project, thinking about the Belle as a postbellum construction tied to Lost Cause ideology and the commercialization of that figure. Refining your topic in this way allowed you to make an argument primarily on the basis of visual evidence enhanced by the context and additional support found in your secondary sources. I can really see how your writing has grown from this entire process (especially in your ability to support your ideas with evidence from secondary sources).

This study is really useful in making sense of Blanche in Streetcar which I am teaching to English school kids!