Rachel Jolivette Brown

Enslaved mothers, powerless under the constraints of slavery, watched helplessly as an unjust institution formed by white men tore their families apart. Slavery impeded responsibilities of black mothers and, in many cases, stripped them of their maternal identity. In the many visual representations of black women in nineteenth century American art and visual culture, very few portrayals exist in which they assume a maternal role with their own children. Instead, surviving representations tend towards stereotypes mediated by whiteness, which, in various ways, claim to ‘legitimize’ the women. Antebellum visual culture supports that notion that contemporaries could only tolerate African American motherhood when validated by white authority. The idea of purely black mothers raising civilized families was inconceivable due to assumptions made about the inherent nature of African Americans and white anxieties concerning the implications of emancipation. Antebellum visual culture, then, reveals that entrenched assumptions about the nature of blackness combined with anxieties about the implications of emancipation to limit the acceptable representations of African American motherhood to those that conform to white authority.

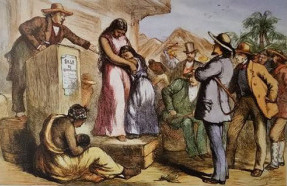

At first glance, Slave Auction in the American South before the Civil War demonstrates the horrifying reality of an enslaved mother being sold separately from her child (Fig. 1). A closer examination, however, reveals another troubling reality: that contemporaries could be sympathetic toward black

motherhood only when the mothers sustain some amount of whiteness. Standing on a wooden auction block, the mother and child’s central placement in the composition make them the focus of the composition. A hatted auctioneer in a coffee-colored coat stands behind a podium that reads “SALE.” He gestures toward the two, indicating their status as purchasable slaves. The way the young girl in her powder blue dress grips her mother’s waist, sinking her head into her bosom forlornly, suggests the family members are being sold away from each other. The mother attempts to console her daughter, but the older woman’s posture and the manner in which she lowers her head convey her grief, for she recognizes this moment as potentially the last interaction she will have with her daughter.

The bottom left portion of the composition contains a parallel pairing of another enslaved mother and child. This mother looks down at her infant in a similar manner, nursing as she waits their turn on the auction block. Like the first mother-child pair, their bare feet and simple clothes conspicuously differentiate them from the surrounding white men dressed in slacks and shined loafers. This, though, is where the physical similarities end, for the differences between the two pairs of figures signal racial difference and an appeal to white sympathies. The lower left mother depicted with a darker, more ethnic complexion, breastfeeds her infant as she sits on the dirt with her legs outstretched. Although mostly hidden by the patterned tignon wrapped around her head, her hair seems short and perhaps coarse. Her child’s hair certainly has a similarly coarse and curly texture. This mother wears a soiled, tattered garment resembling a repurposed bed linen. Her exposed shoulder suggests the frock was fashioned out of necessity, possibly to enable breastfeeding, rather than for stylishness. Furthermore, the casual display of her bare shoulder renders her immodestly dressed according to period sensibilities and therefore less civilized than the fully clothed men surrounding her.

The illustrator renders the centermost mother/daughter pairing literally and figuratively above the other pair. The two are physically elevated, in that they stand on the raised auction block. But they are also metaphorically elevated through compositional hierarchy, arguably because their light skin them tolerable and sympathetic to the viewer. The long, dark, seemingly soft hair shared by mother and child mimics that of a white woman’s locks, and their skin appears almost the same color as that of the white buyer’s. Although barefoot, the women on the block don attire modest in comparison to the woman with an exposed breast seated below. Their long, colorful dresses remain clean, undamaged and therefore appealing, despite the implication of impending slave labor that lingers within the composition.

This image obscures, but does not entirely ignore, the more graphic aspects of slavery. The pair on the auction block seems immediately threatened by the plights of slavery. Fronting the assembly of potential slave masters, a white man in a blue suit positions himself directly in front of the auction block, prepared to claim his purchase. He stands erect with an air of confidence, holding a whip beneath his crossed arms. Although the suited man’s crop remains unused within the scene, his shadow already strikes the back of the young girl, metaphorically alluding to her future as a slave. Additionally, two small figures in the background demonstrate the tortuous purpose of the crop, as a man in a yellow hat beats a male slave. The shirtless slave, hands cuffed behind his back, bends his knees as he braces himself for the painful wale of the whip. The posterior positioning of this particular imagery in comparison to the foreground placement of the women implies that female enslavement tugs more at the heartstrings of abolitionist sympathizers than male enslavement.

The physical differences and variation in compositional focus between the two pairings of mother and child, as well as the details and background suggest an attempt by the artist to render the plight of enslaved mothers and children palatable to white abolitionist sympathizers. The illustrator markedly prioritizes the mother-child pair with fair skin, soft hair and clean appearance, for they would have prompted a stronger response from a white viewer than the darker mother and infant seated in the dirt. Depicting enslaved African Americans with characteristically white features caused the white audience to see themselves within the image of the slave, thus confounding notions of strictly ‘black’ and ‘white’ racial identity.[1] The resulting notion of the “white slave” prompted the fear that slavery might threaten the freedoms of all white people if it continued, thereby framing abolition something necessary to preserve white Victorian culture.[2] The central pair’s whiteness would have appealed to Victorian sentiment, as it implied inherently white traits–things like modesty, virtue and propriety–that stem from idealized womanhood. Due to their whiteness, the violation of the women that takes place in this scene heighten the perception of immorality.[3]

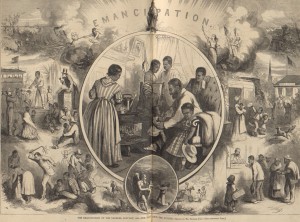

In an engraving published in the January 24th, 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly, political cartoonist Thomas Nast illustrates “The Emancipation of the Negroes, January, 1863 – the past and the future (Fig. 2).”[4] Nast’s image suggests that there exists no ‘normal’ motherhood for African Americans under slavery and, in emancipation, no possibility of family outside Victorian norms. This image also perpetuates racial hierarchies by suggesting emancipation as an act of white benevolence. The composition is organized into three parts: on the left, brutal scenes of enslaved families; in the center, a

domestic scene of a black, middle class family under the banner of “Emancipation;” and finally, scenes of education and employment that will define this family’s life in the future.

The drawings on the left of the composition, each of which illustrates the sufferings of the enslaved, suggest the impossibility of normative family units among enslaved persons. The top image shows the brutal hunting of runaway slaves, ruthlessly chased by bloodthirsty hounds and bullets. The center left image shows the separation of a family at a slave auction. An African-American mother, who has just been purchased, begs her new owner to bid on her husband as well, yet the buyer crosses his arms indifferently, unmoved by the woman’s emotion. Her children sit beside her, weeping, as they mimic their mother’s pleading. His stern, callous demeanor is amplified by the juxtaposition of his indifference and her sorrowful emotion. The image’s sympathies clearly lie with the mother and her family and encourage an emotional response to the unjust act.

In the bottom left corner, Nast details a different manner of destroying a family: violent torture. The harsh blow of a whip causes blood to drip from the mother’s bare back. Her children look down, unable to watch as their shackles render them powerless. Just steps away, her husband cries out in pain as a hot iron brands his dark skin. Smoke rises as his flesh is singed. In an adjacent vignette, a white man on horseback raises a long, sharp object above the head of a runaway slave. This combination of imagery undoubtedly elicits the viewer’s sympathy, but it also depicts slave families as fundamentally fragmented, leaving no possibility in the sphere of slavery for mothers, fathers, and children to exist as a family unit.

These illustrations stand in sharp contrast to the central vignette of the work. Here, Nast depicts the future of African Americans as a result of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation presenting African Americans, including a black family, in environments and engaged in activities that would have been perceived as ideal and thus characteristically white. In this new vision for America, black families will live in simple but respectable homes. Mothers will tend to the house, children will go to school, and fathers will work for wages. In one vignette, two young children wave goodbye to their mother as they eagerly join the crowd of black students shuffling into the public school. Below, Nast illustrates an equally unprecedented scene of black laborers receiving pay from a white cashier. To the left of this scene, Nast contradicts the scene that falls on the opposite side of the small circular frame. The same white man on horseback who chased the runaway slave now interacts with a black man in a thoroughly different manner. Although Nast literally and symbolically elevates the white man, all three men, white and black, tip their hats toward one another as a form of mutual respect. Such a comparison suggests that emancipation will create respectful, if hierarchical, relationships between individuals of different races.

In the main scene of this central vignette, Nast produces an image of a free African-American family cast in the image of the conventionally white, Victorian ideal of family. Gathered in their own home, the father laughs as he bounces his youngest child on his knee while the older daughter lovingly grips his arm, pining for his attention. His son holds an open book, denoting his literacy. Although the viewer sees only her back while she prepares a meal at the stove, the mother’s protruding cheekbones indicate her smiling gaze. An elderly woman, presumably the grandmother, rocks in her chair, while a younger couple chats in the background. The representation of multiple generations highlights the notion that this family has remained intact over time.

Without a careful search, Lincoln’s presence could go unnoticed. Nast strategically hangs a photo of the President above the mantel, just below the sizable inscription reading, “Emancipation.” These two inclusions contextualize the image, subtle reminders that the acceptable black family can only exist under the banner of emancipation- not as an inherent right, but a right given to them by white men. Although this engraving aims to depict freed African Americans in a positive light, it does so while upholding the racial hierarchy instilled by the institution of slavery.

The image joins a national debate, often materialized in visual culture, about the suitability of African Americans for citizenship. This discourse rested on the conviction that all members of a race possessed an essential nature that determined their fitness for citizenship.[5] Yet the image debates black capability in another area, too: Could African Americans function in a normative family unit? Yes, the image suggests, but only with the approval of white authority, hence the presence of Lincoln and the banner of emancipation. In failing to imagine black families of the future outside this paradigm, Noble excludes the possibility of an independent, autonomous and essentially black model of family and motherhood.

In 1867, artist Thomas Satterwhite Noble painted Margaret Garner, which illustrates the widely publicized story of an enslaved mother who committed infanticide (Fig. 3). Just over a decade before Noble completed this painting, Margaret Garner, a mixed-raced house slave, fled from her master’s plantation in Kentucky with her family to seek refuge through the underground railroad.[6] Upon making

Margaret Garner, 1867.

it to Cincinnati, the Garner’s owners and United States Marshals, acting under the Fugitive Slave Act, caught up to them at their safe house. The family barricaded themselves inside as Margaret’s husband tried to ward them off with a shotgun stolen from the plantation.[7] Margaret knew only minutes remained before she would have to face the reality of being returned to a life of slavery. In that moment, Garner decided she would rather see herself and her children dead than enslaved. Using a knife found in the kitchen, she slit the throat of her two-year-old daughter. She wounded her remaining three children, although not mortally, as the slave catchers broke down the barricade and took her into custody.[8]

Over ten years after the indecent, when Noble completed his portrayal of Margaret Garner, her captivating story remained relevant. In this piece, Noble depicts both plight of enslaved mothers and the gruesomeness of Garner’s act in a way that is ostensibly sympathetic to Garner, but also reveals anxieties about the perceived savage nature of African Americans which, without the institution of slavery to keep it in check, threatened both the natural and social order. Noble’s composition depicts the moments after slave catchers have broken down the barricade. Eerie lighting creates a hostile atmosphere, illuminating a distraught Garner and her lifeless children. The four white men positioned to the left wear collared shirts and sophisticated coats, indicating their superior status. The manner in which their feet remain in front of them while they throw their chests back suggests the men have been stopped in their tracks, horrified by the scene in front of them. One man looks back at the others, clearly disturbed, as he points towards the motionless bodies of Gardner’s sons on the floor. Garner’s two younger children, in tattered and frayed attire, tug insistently at her left arm in a way that makes it unclear whether they are begging her to stop or seeking shelter from the intruders. Noble depicts Garner in equally ragged garments and a head wrap that signifies her ethnicity. She stands above her newly deceased children, seemingly oblivious to the younger boys tugging at her sleeve. She mirrors the white man across from her, motioning downward dramatically with a furrowed brow as if to say, “look at what you have caused!”

Upon this completion of this painting, Noble entered a lively, decade-long discourse on whether African-American women were capable of raising a family – a question exacerbated by an existing debate on the morality and necessity of slavery. The legal proceedings resulting from Garner’s act of infanticide played out in the media, creating a public debate in which popular perception seemed divided. Some interpreted her behavior as vicious and animalistic, portraying Garner as less than human. In an article describing the events, the Cincinnati Press reports, “with swift and terrible force she hacked at her child’s throat. Again and again she struck until the little girl was almost decapitated.”[9] Descriptions like these intended to prove that black women lacked a moral code and consequently had the potential for extreme brutality. On the opposing side, abolitionist sympathizers defined the incident as an act of maternal love, attesting to the horrors women faced within slavery. Speaking on behalf of Garner at trial, abolitionist Lucy Stone Blackwell appealed to her audience by saying, “The faded faces of [Garner’s] negro children tell too plainly to what degradation female slaves submit” – a reference to the mixed-race status of both Garner and her children as the product of rape by a white man.[10] Blackwell continued, “Rather than give her little daughter to that life, she killed it. If in her deep maternal love she felt the impulse to send her child back to God… who shall say she had no right to do so?”[11] Blackwell argued that although Garner’s actions were both rash and severe, they were also, most importantly, merciful.

Despite the common knowledge that Garner physically committed the murder, Noble’s interpretation enables the viewer’s sympathy in a number of ways. The artist does not depict Garner engaged in the murderous act, but rather in the regrettable aftermath. With her abject posture, he renders her a victim rather than an assailant. Additionally, Noble refrains from depicting Garner with the murder weapon, highlighting the ambiguity of blame. Although she committed the murder, he suggests, perhaps, that she may not responsible. Furthermore, he replaces Garner’s infant daughter–the child she actually killed–with two fictitious sons. The death of two young, male slaves would have had a larger financial impact, worsening Garner’s act in the eyes of slave owners, but the absence of the murdered infant certainly allows for more sympathy towards Garner.[12]

Although Noble made an allowance for sympathy, the painting does not solely concern maternal sacrifice. Leslie Furth argues that Noble illustrates Garner in such a way that suggests that African-American women were incapable of maternal attachment and, if left to their own devices, a dangerous threat to social order.[13] She demonstrates that Noble’s composition relies on images of “corpse discovery” scenes, popular during the time of this painting’s creation.[14] The men appear stunned and powerless, and though per posture suggests potential victimhood, Garner’s facial expression indicates a mixture of anger and rages, further encouraging the perception of Garner as a ruthless killer.[15] Using their knowledge of the case and the conventions of the popular crime scene images that Furth cites, the viewer might easily interpret Garner’s role as the monstrous murderer while the white men stand by only as witnesses.[16]

Noble completed this painting just two years after the Civil War ended, a time when the prospect of freedom and power for African Americans troubled many.[17] Noble reifies anxieties about the power reversals of both African Americans and women. He does so by portraying Margaret Garner as the consequence of a black woman liberated from white authority. By choosing to illustrate this subject matter, and portraying Margaret Garner in the way that he did, Noble underscores perceptions of African-American women as innately incapable of being maternal and highlights the notion that, without the authority of white men, they are dangerous and subversive.

Despite being deemed incapable of mothering their own children, there did exist a paradigm in which African American women could be maternal: caring for white children under the supervision of whites as a domestic nurse, or ‘mammy.’ The stereotypical role of the mammy, given to female house slaves by their masters, became the only accepted manner in which a black woman could assume a maternal role within a household. George Fuller’s Negro Nurse with a Child (1861), a representative

example of the mammy stereotype, depicts a stereotypical mammy, revealing the trope as a popular portrayal of black women because it did not threaten racial hierarchy (Fig. 4).

In this image, Fuller depicts a common interaction between a mammy figure and her charge. The black woman, dressed in maroon with her shoulders cloaked in a red shawl, sits in a wooden chair. As she sits, she detangles the long blonde locks of her porcelain white charge. Her pale skin and flowing tresses contrast sharply with her nursemaid’s dark complexion and the implication of course curls concealed beneath her white and blue pattern head wrap. The contrast created by their hair highlights their racial differences. The young girl, undisturbed her nurse’s combing, appears distracted by the doll in her hands. In the background, the accessorized wooden dresser identifies the setting as the young girl’s bedroom.

Although Fuller depicts the black woman as a nurturer, he maintains the racial hierarchy. The viewer would intuitively recognize the mammy figure as a subordinate under the direction of a white superior. Typically, even with a dynamic between an adult and a child, the white individual is physically positioned above their black counterpart, symbolically acknowledging the hierarchy.[18] In Fuller’s painting, the mammy figure sits above the white child, but only to perform the menial task of combing her hair, diminishing any possible perception of dominance. Fuller’s depiction of the mammy, type and others like it, confirms that black maternal roles were only accepted if in service and submission to whites.

While the trope is, in many ways, defined by her service, “mammy” connotes much more than simply “enslaved babysitter.” A prescribed set of physical attributes and an obsequious demeanor defined the mammy figure as an enduring American cultural icon. In a host of representations in both fine art and popular visual culture from the nineteenth-century through the present day, the mammy endures as a is a heavy set, dark-skinned woman, content and completely consumed with her duties as a caretaker, no different from the subject of Fuller’s painting. These features neutralize her sexuality. The existence of mixed-race children confirms the reality of sexual relations between masters and slaves, but white men were, at least in theory, more drawn to the light-skinned women with conventionally Caucasian features.[19] The mammy figure’s dark complexion and overweight physique rendered her undesirable according to conventional nineteenth-century standards, making sexual advances from the man of the house less likely and easing the worry of his wife.[20]

Moreover, in addition to not being allowed to threaten a white woman’s place as romantic partner to her husband, the mammy figure was also not allowed to threaten her role as a mother. Although the mammy fed, bathed and played with their charges, she did so at the request of white authority. These seemingly maternal tasks were understood as labors no different from washing clothes or sweeping floors and secured the role of the mammy as a worker and not a surrogate mother.[21] Thus, black women would be seen as motherly only when the maternal tasks they performed were for white children at the command of a white authority and only when those tasks could be understood as the result of mandatory labor rather than maternal love.

In antebellum visual culture, black motherhood was only acceptable when mediated by white authority. Comparing and contrasting the two mother-daughter pairs in the slave auction illustration suggests that nineteenth-century viewers found sympathizing with a dark-skinned black mother lacking white legitimacy nearly impossible. Thomas Nast’s engraving indicates only by adhering to the white Victorian ideal and under the banner of an emancipation bestowed upon African Americans by beneficent whites could the general public entertain the possibility of a positive portrayal of black motherhood. Indeed, even after emancipation, Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s portrayal of Margaret Garner functions as a warning of the dangers associated with empowering black mothers, suggesting the necessity of white supervision to prevent upheaval of both nature and society. Despite the considerable progress that society has made on the fronts of race and gender since the Civil War, among all of the paradigms of black motherhood that exist in visual culture, the mammy figure has endured as an American cultural icon, suggesting that, with regard to the depiction of black motherhood, much progress still remains to be made.

[1] Mary Niall Mitchell, “‘Rosebloom and Pure White,’ or so It Seemed,” American Quarterly 54 (2002): 380.

[2] Ibid, 367-377.

[3] Ibid, 378.

[4] Rob Kennedy and Harp Week, “On January 24, 1863, Harper’s Weekly Featured a Cartoon about the Emancipation Proclamation” (New York Times Learning Network).

[5] Furth, “The Modern Medea” and Race Matters, 45-46.

[6] Steven Weisenburger, Modern Medea: A Family Story of Slavery and Child-Murder from the Old South (New York: Hill and Wang, 1998), 61.

[7] Wesidenburger, Modern Medea, 72.

[8] Ibid, 74-75.

[9] Furth, “The Modern Medea” and Race Matters, 38.

[10] Ibid, 38.

[11] Ibid, 38.

[12] Ibid, 40.

[13] Ibid, 49.

[14] Ibid, 41.

[15] Ibid, 39.

[16] Ibid, 51.

[17] Ibid, 38.

[18] Ibid, 51.

[19] Mary Niall Mitchell, “‘Rosebloom and Pure White,’ or so It Seemed,” American Quarterly 54 (2002): 380.

[20] Little Star, “The Strong Black Woman Re/Defined: A Theatrical Exploration of Stereotypes” (BFA diss., University of Louisville, 2000),18.

[21] Ibid, 60.

Works Cited

Furth, Lelsie. “The Modern Medea” and Race Matters: Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s “Margaret

Garner.” American Art 12, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 37-57.

Patton, Phil. “Mammy, Her Life and Times.” American Heritage 44, no. 5 (September 1993):

78-84.

Halloran, Fiona Deans. The Power of the Pencil: Thomas Nast and American Political Art. PhD

diss., UCLA, 2005.

Howlett, Scott W. “‘My child, him is mine’: Plantation slave children in the Old South” PhD diss. University of California, Irvine, 1993.

Jordan-Zachery, Julia Sheron. Black Women, Cultural Images, and Social Policy. New York:

Routledge, 2009.

Jones, Jacqueline. Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family from Slavery to the Present. New York: Basic Books, 1985.

Kennedy, Rob, and Harp Week. “On January 24, 1863, Harper’s Weekly Featured a Cartoon

about the Emancipation Proclamation.” The New York Times Learning Network. Last

modified January 24, 2001. Accessed November 28, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/harp/0124.html#explanation

Morgan, Jo-Ann. Uncle Tom’s Cabin as Visual Culture. Columbia : University of Missouri

Press, 2007.

Little, Star Xavier. “The Strong Black Woman Re/Defined: A Theatrical Exploration of

Stereotypes” BFA diss., University of Louisville, 2000.

Ritchie, Natalie. “The Mammy Myth: Mattie Mooreman’s Story,” edited by Nan Mullenneaux.

Fall 2012.

The Story of English. “The Mother Tongue.” Directed by William Cran. Written by Robert

MacNeil, Robert McCrum and William Cran. PBS, 1986.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Boston: John P. Jewett & Co., 1852.

Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly. Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory. Ann

Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2011.

Weisenburger, Steven. Modern Medea: A Family Story of Slavery and Child-Murder from the

Old South. New York: Hill and Wang, 1998.

Yes, Ma’am. DVD. Directed by Gary Goldman.United States: Filmakers Library, 2002. Film

Rachel, I really like your essay! The visual analyses leave no stone unturned when it comes to the content of the image. I also think that you do a great job of presenting your case – you use visual imagery to support your point, which takes on a very delicate topic. Yet, I think you do a really good job of remaining unbiased when analyzing the Mammy mother figure.

This is an excellent essay and I agree with the previous comment that the visual analysis is particularly good. I would also like to point out that this essay strikes the perfect balance between emotional language and scholarly rigor (Bravo). The only thing that I can think to suggest that might improve it, would be to define terms such as ‘identity.’ Nonetheless, you should be proud. S.S.

Very thorough analysis of images – great work!

Rachel, like others, I was particularly impressed with your visual analysis of the individual works in this essay. You took on a very challenging topic, and you should be proud of the finished product and all your hard work. The transformation between your first draft and your final essay is amazing!