Rachel Jolivette Brown

Margaret Garner, 1867.

The infamous tale of runaway slave Margaret Garner’s valiant attempt to rescue her children from the institution of slavery inspires Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s captivating painting, Margaret Garner (Fig. 1). This work intensely illustrates the moments after slave catchers uncover Garner and her family in a safe house for fugitive slaves in Cincinnati. Eerie lighting creates a hostile atmosphere, illuminating a distraught Garner and her lifeless children. The four white men positioned to the left wear collared shirts and sophisticated coats, indicating their superior status. They appear horrified by the scene of death in front of them. The manner in which their feet remain in front of them, while they throw their chests back suggests the men have been stopped in their tracks. One man looks back at the others, clearly disturbed, as he points towards the motionless bodies of Gardner’s sons on the floor. Garner’s two younger children, in tattered and frayed attire, tug insistently at her left arm in a way that makes it unclear whether they are begging her to stop or seeking shelter from the intruders. Noble depicts Garner in equally ragged garments and a head wrap that signifies her ethnicity. She stands above her newly deceased children, seemingly oblivious to the younger boys tugging at her sleeve. She mirrors the white man across from her, motioning downward dramatically with a furrowed brow as if to say, “look at what you have caused!” Noble’s portrayal of Garner renders her physically responsible for the murder, but suggests an ambiguity in blame.

Although convincing, details within Noble’s composition distort truth. Margaret Garner was, in fact, a mixed-raced fugitive slave who took the life of her own child, but many details of her narrative have been amended. Noble definitely did not take making these modifications lightly. Multiple sketches and an additional painting with the

young men’s bodies in differing positions prove that Noble applied a great amount of consideration to the details of his composition (Fig. 2).[1] In 1856, a decade before the completion of the painting, Garner fled from her master’s plantation in Kentucky with her family to seek refuge through the Underground Railroad.[2] Upon making it to Cincinnati, Ohio, the Garner’s owners and United States Marshals acting under the Fugitive Slave Act caught up to them at their safe house. The family barricaded themselves inside as Margaret’s husband, Robert, tried to ward them off with a shotgun stolen from the plantation.[3] Margaret knew only minutes remained before she would have to face the reality of being returned to a life of slavery. In that moment, Garner decided she would rather see herself and her children dead than enslaved. Using a knife found in the kitchen, she slit the throat of her two-year-old daughter. She wounded her remaining three children, although not mortally, as the slave catchers broke down the barricade and took her into custody.[4]

Upon the completion of Noble’s painting in 1867, he entered a lively, decade-long discourse on whether African-American women were capable of raising a family – a question exacerbated by an existing debate on the morality and necessity of slavery. The legal proceedings resulting from Garner’s act of infanticide played out in the media, creating a public debate in which popular perception seemed divided. Some interpreted her behavior as vicious and animalistic, portraying Garner as less than human. In an article describing the events, the Cincinnati Press reports, “with swift and terrible force she hacked at her child’s throat. Again and again she struck until the little girl was almost decapitated.”[5] Descriptions like these intended to prove that black women lacked a moral code and consequently had the potential for extreme brutality. On the opposing side, abolitionist sympathizers defined the incident as an act of maternal love, attesting to the horrors women faced within slavery. Speaking on behalf of Garner at trial, abolitionist Lucy Stone Blackwell appealed to her audience by saying, “The faded faces of [Garner’s] negro children tell too plainly to what degradation female slaves submit” – a reference to the mixed-race status of both Garner and her children as the product of rape by a white man.[6] Blackwell continued, “Rather than give her little daughter to that life, she killed it. If in her deep maternal love she felt the impulse to send her child back to God… who shall say she had no right to do so?”[7] Blackwell argued that although Garner’s actions were both rash and severe, they were also, most importantly, merciful.

Despite the common knowledge that Garner physically committed the murder, Noble’s interpretation enables the viewer’s sympathy in a number of ways. The artist does not depict Garner engaged in the murderous act, but rather in the regrettable aftermath. With her abject posture, he renders her a victim rather than an assailant. Additionally, Noble refrains from depicting Garner with the murder weapon, highlighting the ambiguity of blame. Although she committed the murder, he suggests, perhaps, that she may not responsible. Furthermore, he replaces Garner’s infant daughter–the child she actually killed–with two fictitious sons. The death of two young, male slaves would have had a larger financial impact, worsening Garner’s act in the eyes of slave owners, but the absence of the murdered infant certainly allows for more sympathy towards Garner.[8]

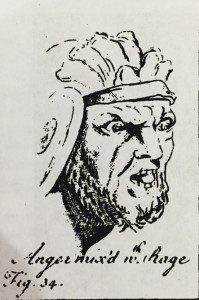

Although Noble made an allowance for sympathy, he did not intend for this painting to solely concern maternal sacrifice. Leslie Furth argues that Noble illustrates Garner in such a way that suggests African American women were incapable of maternal attachment and, if left to their own devices, a dangerous threat to social order.[9] With this, Margaret Garner becomes a manifestation of white anxieties. Garner’s masklike facial expression suggests Noble was influenced by Charles Le Brun’s painter’s manual entitled A Method to Learn to Design the Passions, in

which he demonstrates human emotions through facial expression. Noble seems to use a mixture of anger and rage in his portrayal of Garner (Fig. 3).[10] This detail undoubtedly supports the portrayal of Garner as an animalistic killer. Additionally, Furth demonstrates that Noble’s composition relies on images of “corpse discovery” scenes, popular during the time of this painting’s creation.[11] The men appear stunned and powerless, and though per posture suggests potential victimhood, Garner’s facial expression indicates a mixture of anger and rages, further encouraging the perception of Garner as a ruthless killer.[12] Using their knowledge of the case and the conventions of the popular crime scene images that Furth cites, the viewer might easily interpret Garner’s role as the monstrous murderer while the white men stand by only as witnesses.[13]

The purpose of Noble’s distortions of Margaret Garner’s story continues to be debated. Although Garner’s story spoke to abolitionists and was often used to show the institution of slavery in a negative light, Noble himself was not known to be in favor of emancipation.[14] He may have intentionally portrayed Garner this way to make a statement, but this depiction could also simply mean that Noble was a product of his time. Nonetheless, Margaret Garner provokes the viewer to question their perception of Garner’s act of infanticide by highlighting the ambiguity of blame, while simultaneously depicting white anxieties.

[1] Leslie Furth, “The Modern Medea” and Race Matters: Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s “Margaret Garner”, American Art 12, no. 2 (1998): 39.

[2] Steven Weisenburger, Modern Medea: A Family Story of Slavery and Child-Murder from the Old South (New York: Hill and Wang, 1998), 61.

[3] Ibid, 72.

[4] Ibid, 74-75.

[5] Furth, “The Modern Medea” and Race Matters, 38.

[6] Ibid, 38.

[7] Ibid, 38.

[8] Ibid, 40.

[9] Ibid, 49.

[10] Ibid, 39.

[11] Ibid, 41.

[12] Ibid, 39.

[13] Ibid, 51.

[14] Ibid, 37.

Works Cited

Furth, Lelsie. “”The Modern Medea” and Race Matters: Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s “Margaret

Garner”” American Art 12, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 37-57.

Simkins, Anna. The Function and Symbolic Roles of Hair and Headgear Among Afro-American

Women: A Cultural Perspective. PhD diss., University of North Carolina, 1982.

Weisenburger, Steven. Modern Medea: A Family Story of Slavery and Child-Murder from the

Old South. New York: Hill and Wang, 1998.