Rebecca Villalpando

Sitting with her back toward the audience, Jacques Lucien Amans’ Creole in a Red Headdress (figure 1) turns her face to meet the viewers’ gaze, her bare shoulders and slight smile adding an air of coquettish sensuality to the painting. Though dressed rather simply in a white long-sleeved off-the-shoulder peasant blouse and brown skirt, the woman visually entices viewers as the bright red of her headdress enhances the creamy texture of her café au-lait skin tone. Though little is known about the portrait of this young mixed-race woman, her alluring, unbroken gaze renders her as a subject of much intrigue and speculation.

In many ways, the unnamed woman in Amans’ Creole in a Red Headdress embodies the tricky, conflicting, and sometimes paradoxical portrayals of women in the portraiture of antebellum Louisiana. Portraits—especially those made fashionable by European painters who catered to the city’s growing clientele—constituted one way in which New Orleans’s citizens established their wealth and social status. Although this painting greatly differs from countless other portraits of women in the antebellum United States, portraits of women of color were not uncommon in antebellum New Orleans, a fact that makes the unique attributes of this work all the more striking. A study of Amans’ Creole in a Red Headdress, understood within the context of more conventional portraits like those of Amans’ white female sitters as well as portraits of other free women of color, reveals both the work’s complicated status as a “portrait” and the problematic portrayals of mixed-race women in antebellum Louisiana in general. Though New Orleans portraiture had purpose in recording contemporary antebellum history, depicting wealth, and portraying subjects of the artist’s interest, it also carried implicit messages about race, gender, and political climate in a nation poised at the threshold of war.

The Rise of Portraiture in New Orleans

Portraits often provide a window into personal histories within larger social histories. Scholar Richard Brilliant writes, “Portraits exist as the interface between art and social life and the pressure to conform to social norms enters into their composition because both the artist and the subject are enmeshed in the value system of their society.”[1] With this in mind, portraits then offer a critical index of their era’s social norms, political influences, and stylistic preferences.

Antebellum New Orleans’ portraiture exemplifies how portraits act at the junction between social life and art because the paintings reflect the colorful history of the city and the resulting tricky social and racial relations. In the eighteenth century, as colonial control over New Orleans changed from French to Spanish,[2] people living as slaves gained more power for social mobility and the ability to buy their freedom. These individuals and their descendants, along with an influx of French-speaking refugees from Saint-Domingue by way of Spanish Cuba,[3] accounted for the abundance of free people of color in New Orleans and its surrounding parishes.[4] The population of free people of color in Louisiana peaked in 1840 at 25,500, however that number decreased significantly as the Civil War approached and the social and political climate of Louisiana changed, becoming less tolerant of the coexisting of races.[5] Still, for a city situated in the Deep South, this significant presence of free people of color living in the cosmopolitan port city of New Orleans was very unique.

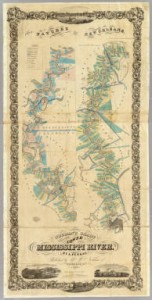

Despite its cosmopolitan feel and substantial population of free people of color, New Orleans simultaneously rooted itself in a cotton and slave-based economy. As the epicenter of cotton production shifted toward the newer southwestern states in the early to mid-nineteenth century, the city’s importance increased in the slave-plantation economy of the American South.[6] Marie Adrien Persac’s map, Norman’s Chart of the Lower Mississippi River (Figure 2), represents this growing prominence, detailing the location, name and owners of all the plantations and depicting the effects of this plantation economy on the development of New Orleans and its surrounding parishes.[7] With these factors in mind, when the Civil War approached, Louisiana acted in accord with other southern slave states and voted to secede from the Union on January 26, 1861.[8] Some of the best visual representations of these complex political and social realities of antebellum New Orleans—especially in terms of gender and race—rest in the countless portraits of women created in Louisiana in the early nineteenth century.

Portraiture dominated the art scene of the early nineteenth century in both the city and plantation country of southern Louisiana.[9] This popularity developed for a myriad of reasons. Members of antebellum Louisiana society fixated on social standings, especially finding stratification regarding the term “creole.” The parameters of this identifier grew muddled as tensions between the French population and the American sector in New Orleans peaked and also as the phrase began to acquire complex racial implications in the early to mid 1800s.[10] Louisiana citizens’ desire to portray their own cultural or racial identity as they saw it resulted in the use of portraiture as visual reportage. Citizens used commissioned portraits to clarify their own self-identification to the rest of society. In a similar vein, portraits also signified wealth, and commissioning a portrait reified that wealth through visual representation. As seen through Persac’s map, an abundance of wealthy plantation owners established themselves near New Orleans in the early nineteenth century, and these individuals, along with the wealthy patrons living in the city accounted for a surge in commissions.

With the early nineteenth century demand for portraiture came the supply of eager painters. Thus many artists—both local painters and artists from abroad—found steady work painting the businessmen, plantation owners, political leaders, their wives and daughters, and well-to-do free people of color, who lived along the Mississippi. The aforementioned Jacques Lucien Amans’ and his notable contemporaries, Jean-Joseph Vaudechamp and Francois (Franz) Fleischbein, comprised a prosperous trio of portraitists who successfully catered to local tastes. All three of these talented European painters traveled to the American South after successful shows in Europe, aiming to capitalize on the booming industry of portraiture in the Mississippi delta.

Each artist painted with a distinctive style and level of finesse, but all found popularity in New Orleans particularly because they painted in accord with the popular styles in Europe. Wealthy sitters—specifically those identifying as French Creole—emulated Europe’s elite and had their portraits painted in popular European styles to bolster their standings in New Orleans society. The portraits signified prosperity and paid homage to their patrons’ European roots.[11]

Conventional Portraits of Female Sitters

While his contemporaries explored more gestural painting and realism, Jacques Amans painted consistently in continuation with the style of the works he previously exhibited in The Salon of Paris, utilizing refined neoclassical techniques.[12] His work, however, maintains an overall warmer quality, demonstrating a more delicate touch. Amans’ paintings feature less direct and severe characteristics than that of typical highly linear neoclassical work. This elegant, flattering, and markedly European painting style suited the desires of Amans’ sophisticated wealthy sitters, which included the wives and daughters of New Orleans social elite and French émigré plantation owners.[13]

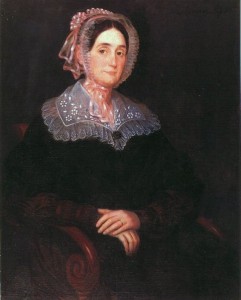

In Amans’ many portraits of female white sitters, he portrays their figures in three-quarter length, primarily facing forward, their bodies slightly angled. His Portrait of Josephine Roman Aime, c. 1838, (figure 3) exemplifies his standard work. The woman poses against a nondescript, dark grey backdrop, wearing a modest long-sleeved ebony-colored dress with a pleated white Chantilly lace collar. Her light pink tulle bonnet frames her face in a wreath of ruffles. Amans uses his neoclassical technique to meticulously render Aime’s rich and modest fashions, highlighting her elevated social status and virtuousness. Through Aime’s high-strung collar and bonnet, her stoic expression, and the flattering neoclassical light in which she is painted, we get a sense of her position in society. Josephine Roman Aime embodied the wealthy French Creole planter class. As the sister of JT Roman (of Oak Alley Plantation fame), and the wife of sugar tycoon Valcour Aime, the prosperous socialite resided in her palatial plantation home known as “Le Petit Versailles.”[14] Amans articulates Aime’s elevated social status through small details like the delicate fabric of her bonnet and dainty lace of her collar. According to scholar Judith H. Bonner, the plain background used here was typical for elegant portraiture displayed in the grand homes of the antebellum South,[15] and Aime clearly lived in one of the grandest antebellum homes in the area where this portrait could hang (the estate’s extensive plot of land can be seen on the Persac map under “Valcour Aime; St. James Refinery”). We also know Aime holds a measure of European sentimentality because her estate was affectionately known as “Le Petite Versailles,” and she—or her husband, nicknamed Louis the XIV of Louisiana—selected the École des Beax-Arts trained Amans as her portraitist.

Amans’ Creole in a Red Headdress certainly stands in contrast to his portrait of Josephine Aime; however, the painting is far from the only depiction of a creole woman of color in this period. Like their white counterparts, many free women of color sat for portraits that, in contrast to Amans’ Creole in a Red Headdress, actually portrayed them with a sense of dignity, pride, and agency. These portraits present the women’s likeness and personality in a formal manner, painting them as individuals with decorum and quiet confidence, and in a manner virtually indistinguishable from that in which white female sitters were depicted. They are, by definition, portraits. As scholar William Keyse Rudolph affirms, many portraits of New Orleans sitters of color “follow dominant conventions of representation that matter-of-factly represent appearance, rather than Otherness.”[16]

For example, in Antoine Louis Collas’ 1829 Portrait of A Free Woman of Color Wearing a Tignon[17] (figure 4), the sitter exudes confidence, wealth, and gentility. The work is apparently self-commissioned,[18] as evidenced by the sitter’s perceived control in the manner and style of the painting. The sitter dresses modestly, wearing a simple black gown with a lacey white shawl. Aside from her brown skin, only the tignon she wears—a trademark of free women of color that will be discussed later—signifies her racial status; however, its bright yellow and green striped pattern render it as a beautiful fashion statement, the rich fabric and design complementing her face somewhat like decorative jewelry. This lush fabric, the small gold trinket box she holds, and the portrait itself announce the woman’s wealth and status. The sitter poses with regal refinement and a strong sense of self as the artist paints her in the same conventional style used for white female sitters. This Portrait of A Free Woman of Color Wearing a Tignon then becomes the antithesis of Amans’ Creole Woman. Rather than depicting a suggestively posed, scantily clad, possibly imagined woman, it portrays a real life sitter dressed modestly and posed with a sense of pride and dignity.

Franz Fleischbein, an aforementioned contemporary of Jacques Amans, creates another visual representation of a dignified free woman of color in a tignon in his 1837 Portrait of Betsy, a captivating, thought-provoking image. Betsy was actually Fleischbein’s housekeeper,[19] making the motivation for painting her unclear. Did Betsy commission this picture on her own? Was Fleischbein painting her out of affection for a well-liked household servant, out of curiosity, or, perhaps, even in an attempt to exoticize her much like the figure in Amans’ Creole in The Red Headdress?

Peeking from the corners of her eyes, Fleischbein’s Betsy (Figure 5) poses proudly for her portrait. Two tufts of her espresso-hued, curly hair spill out from the confines of her ornately wrapped, bright yellow tignon. She wears a simple black dress with a ruched white collar. Her pearl and diamond floral broach and matching earrings highlight her soft tan skin and glossy brown eyes. Betsy’s smile carries a degree of intrigue, her side-eyed gaze adding to her somewhat mischievous whimsy.

Similarly to Jacques Amans’ 1838 Portrait of Josephine Roman Aime (figure 3), Betsy poses against a classically bare nondescript, dark grey backdrop and wears a high-strung pleated white collar. The collar signifies modesty and virtue. With this in mind, Fleischbein paints Betsy in a way that is more respectful than exoticized. She wears pious, rich fashions, highlighting her beauty, and Fleischbein paints her in the same manner as he might any white patron. Fleischbein gives his painting somewhat of an intimate feel due to the evident hints of Betsy’s personality that come through in her playful sideways gaze, which, though somewhat coquettish, is not directly sexual in nature (her gaze is not necessarily a flirtatious “come hither”). Betsy, though coy, carries an air of regal refinement. The artist then seems more interested in capturing Betsy’s expression and personality than the hue of her skin tone. Betsy’s pose and iconic unbroken gaze that appears to follow the viewer, along with the similar position of the hands,

triangular composition, and comparable furtive smile, recall the posture and expression of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (figure 6), though whether Fleischbein invokes this most famous work of the Renaissance master earnestly or playfully remains open to question.

The regal portrayal of both Collas’ sitter and Fleischbein’s Betsy demonstrate a significant departure from the sexualized depiction of Amans’ Creole in a Red Headdress. The images—decidedly portraits—portray the sitters’ personalities and clarify their own self-identification to the rest of society. These women do not classify themselves as hyper-sensual objects, but rather as well-to-do, morally upstanding people.

Amans’ Creole Woman: Portrait or Type?

Though Amans painted scores of conventional portraits of antebellum sitters,[20] his unconventional work, Creole in a Red Headdress (figure 1), remains the most recognized piece created during his time in pre-Civil War New Orleans. The painting simultaneously includes definitive features of Amans’ signature style while also utilizing a composition and subject matter inconsistent with his typical portraiture, ultimately perpetuating stereotypes of mixed-race women in antebellum Louisiana and leaving the painting’s status as a “portrait” open to question.

In Creole in a Red Headdress, the juxtaposition of the sitter’s skin tone and bright red headdress highlight Amans’ signature softer, more colorist approach to the traditional neoclassical style seen in all of his works. However, the figure sits with her back toward the audience, as opposed to a typical frontal or slightly turned composition. As she twists around to stare back at the viewers, her blouse falls suggestively low from her shoulder—a direct opposition to the modest high necklines featured in his Portrait of Josephine Roman Aime. These risqué details amplify common stereotypical perceptions of mixed-race women in New Orleans. The view of mixed-race women as both exquisitely beautiful and also sexually available or erotic materialized itself through various pieces of art and literature. While the artistic renderings and theatrical stories of the “Tragic Octoroon”[21]—an archetypal character of one-eighth African ancestry—detail the legendary beauty of ill-fated mixed-race women, less sympathetic popular perceptions deemed mixed-race women as promiscuous sirens who corrupted otherwise upstanding white gentleman with their irresistible charms.

Evidence of this perception can be seen not only in the dress and demeanor of Amans’ creole woman but also in her red tignon, a headscarf worn—under penalty of law—by women of color in Louisiana. In 1786, Spanish colonial Governor Don Esteban Miró passed this sumptuary law enforcing “appropriate” public dress amongst women of color, free and enslaved.[22] In his edict, Miró describes, “free negro and quadroon women,” as “detrimental,” referring to them as the, “the product of their licentious life without abstaining from carnal pleasures.”[23] Miró was, “Suspicious of their indecent conduct [and] the extravagant luxury in their dressing” (Edict of Good Government, 107). In an attempt to temper their attractiveness to white men and associate them with enslaved people who wore kerchiefs, free women of color were ordered to cover their legendarily beautiful hair, and to refrain from “[excessive attention to dress]”(107). Miró’s early edict responded to the perception of mixed-race women in New Orleans as “licentious” and sexually immoral and the bright crimson hue of this creole seductress’ tignon underscores these associations. That said, through wrapping their hair in sumptuous fabrics (and, perhaps, drawing influence from the West African gélé), women of color, like those featured in the portraits by Collas and Fleischbein, transformed this object of constraint into an enduring trademark, one of revolutionary beauty and pride. In many ways this tignon became a symbol of solidarity and a cultural asset.[24]

While her tignon is one of the most visible symbols of her difference from white sitters, Amans portrays the figure in Creole in a Red Headdress as different from other portrait sitters in a multitude of ways—most noticeably her twisting body position, exposed skin, and flirtatious demeanor. This begs the question: can the Creole in a Red Headdress be considered a portrait at all?

By definition portraiture produces a recognizable image designed to capture the physical, and perhaps personality, traits of a specific individual.[25] In the early nineteenth century, most traditional portraits depict the sitter facing forward, either sitting at three-quarter length, two-thirds length, or standing. Sometimes a portrait, rather like an inventory, records the individual’s wealth and status or heroism.[26] Portraitists provide this evidence through the manner in which a sitter is dressed, the setting in which they sit, or through more overt displays of their possessions. Portraits are markedly different from typological images. Scholar Brian Wallis asserts that, “The ‘type’ discourages style and composition, seeking to present the information as plainly and straightforwardly as possible.” Though types mask their “subjective distortions in the guise of logic and organization,” Wallis asserts that pseudo “objectivity is the goal…the typological image appears to have no author.”[27] That said, Wallis goes on to say the creator of the typological image denies their subject any sense of personhood, stating, “The emphasis on the body occurs at the expense of speech”(Wallis, 54).

Thus, Amans’ Creole in a Red Headdress can be defined as both a portrait and also as an exoticized, typological depiction of a mixed-race woman. On the one hand, the sitter wears a tignon, which signifies her identity and social status in accordance with the definition of portraiture. Unlike Wallis’s definition of type, the image is overtly subjective and carries the visible touch of the artist’s style. On the other hand, rather than facing them head-on, the woman turns around to look back at viewers in a pose and composition atypical of nineteenth century portraiture. Her profusion of exposed skin puts emphasis on her body over her personal identity, a significant characteristic of typological images. Still, other definitive questions remain. Does this painting portray her actual likeness, personality, and mood? Or does it portray Amans’ preconceived ideas about what she should look like, the personality she should evoke, and the come-hither mood her gaze should imply? Is this even a depiction of a woman who actually existed at all or a product of Amans’ fantasy?

The fact that the “creole woman” remains nameless fuels the notion that this painting is merely a typological, imagined amalgamation of stereotypical conceptions of the sexualized, loose-moraled mixed-race woman. Even if this is a depiction of a real woman who existed in the era, the erotic, flirtatious demeanor of the portrait does not suggest a sense of the sitter’s control over her representation. While the painting depicts certain defining aspects of her identity like her tignon, it cannot be conclusively called a portrait because the sitter is constructed as silent with no sense of personhood. Wallis asserts that a portrait must be painted by an artist who views their sitter’s life empathetically or from their point of view. Especially in the case of people of color, Wallis states that a portraitist must see these sitters, “not as representatives of some typology, but as living, breathing [people].”[28] Based on Wallis’s definition, Amans’ Creole Woman should not be considered a portrait, but rather more of a typological image.

Still, the painting cannot conclusively belong to either category. While the artist depicts a mixed-race woman in an impersonal, stereotypical, and ultimately typological manner, Amans’ artistic touch is evident throughout and he makes no effort to downplay his signature style to produce an objective typological image. Perhaps, rather than falling into one classification, Creole in a Red Headdress exists as a unique hybrid of portrait and type that reflects the liminal position of mixed-race women in antebellum society. Through analyzing images of female sitters created by Jacques Amans and his contemporaries and reconsidering the status of his Creole in a Red Headdress as a portrait within this context, we see a clearer picture of the unique social tensions in New Orleans as they pertained to race and gender. Through the vehicle of portraiture, this study provides an interesting view of the social climate in antebellum New Orleans as Louisiana headed toward secession.

[1] Frazier, Nancy. “Portraits/Portraiture.” The Penguin Concise Dictionary of Art History. New York: Penguin Reference, 2000. Print.

[2] Schweninger, Loren. “Free People of Color.” KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Ed. David Johnson. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 28 Apr 2011.

- During the 18th century, Louisiana was a colony of France from 1718-1769, then a colony of Spain from 1769-1893. It became a US territory after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

[3]Lachance, Paul. “The 1809 Immigration of Saint-Domingue Refugees to New Orleans: Reception, Integration and Impact.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 29.2: 109-44. JSTOR. Web.

- In 1809, three thousand French-speaking Saint-Domingue refugees fled from Spanish Cuba to New Orleans due to hostilities between Spain and France as the Napoleonic Wars escalated.

[4] Sacher, John M. “Antebellum Louisiana.”KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Ed. David Johnson. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 28 Jul 2011.

- Most free people of color lived in New Orleans, however a significant colony of people lived in the Cane River region.

[5] Sacher, John M. “Antebellum Louisiana.”KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Ed. David Johnson. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 28 Jul 2011.

[6] Marler, Scott P. “Merchants and the Political Economy of Nineteenth-Century Louisiana: New Orleans and its Hinterlands.” Order No. 3256718 Rice University, 2007. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. Web. 1 Mar. 2015.

[7] “Paintings, Prints, and Photographs.” The Louisiana Landscape 1800 – 1969: September 14 – November 15, 1969; Anglo-American Art Museum; Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Baton Rouge, 1969. Page 9. Print.

[8] Sacher, John M. “Antebellum Louisiana.”KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Ed. David Johnson. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 28 Jul 2011.

[9] McAlear, Donna. “Portraiture, Landscapes, and Marine Scenes in Nineteenth-Century Louisiana.” Collecting Passions: Highlights from the LSU Museum of Art Collection. Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Museum of Art, 2005. Print. Page 40, Section called Portraiture, Landscapes, and Marine Scenes in Nineteenth-Century Louisiana.

[10] Dominguez, Virginia. “Social Classification in Creole Louisiana.” American Ethnologist 4.4 (1977): 589-602. JSTOR. Wiley on Behalf of the American Anthropological Association. Web. 2 Mar. 2015. <http://www.jstor.org>.

- When Louisiana became an American state in 1812, the French identified as Creole to distinguish themselves from the Americans—hence the formation of the distinctive Vieux Carre (French Quarter) and the American Sector. However, the term later referred to those born in Louisiana, applying to natives of both French and American descent. Because the definition of Creole never required “purity” of racial ancestry and many free people of color also identified as Creole due to either native birth or French-colonial ancestry, many northerners began to generalize the term and believed it described only mixed-race people who were culturally French in Louisiana. This dissatisfied Creoles who were not of African descent but rather American or French natives of Louisiana. While the term Creole actually encompassed many more people than mixed-race individuals during the antebellum, the definition continues to change, often times in accordance with the northern generalization.

[11] Lewis, Richard Anthony. “Jean Joseph Vaudechamp.” KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Ed. David Johnson. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 11 Jan 2011.

[12] Tucker, Mary L. Jacques G.L. Amans, Portrait Painter in Louisiana, 1836-1856. Thesis. Tulane University of Louisiana, 1970. New Orleans: Tulane U, 1970. Print.

[13] Lewis, Richard Anthony. “Jacques Amans.” KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Ed. David Johnson. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 11 Jan 2011.

[14] Platt, R. Eric. “Valcour Aime.” KnowLA Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Ed. David Johnson. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 18 Sept. 2014.

[15] McAlear, Donna. “Portraiture, Landscapes, and Marine Scenes in Nineteenth-Century Louisiana.” Collecting Passions: Highlights from the LSU Museum of Art Collection. Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Museum of Art, 2005. 40-44. Print.

[16] Rudolph, William Keyse. In Search of Julien Hudson: Free Artist of Color in Pre-Civil War New Orleans. New Orleans: Historic New Orleans Collection, 2010. 71. Print.

[17] Rudolph, William Keyse. In Search of Julien Hudson: Free Artist of Color in Pre-Civil War New Orleans. New Orleans: Historic New Orleans Collection, 2010. 72. Print.

[18] Rudolph, William Keyse. In Search of Julien Hudson: Free Artist of Color in Pre-Civil War New Orleans. New Orleans: Historic New Orleans Collection, 2010. 71. Print.

[19] Rudolph, William Keyse. In Search of Julien Hudson: Free Artist of Color in Pre-Civil War New Orleans. Page 42.

[20] Tucker, Mary L. Jacques G.L. Amans, Portrait Painter in Louisiana, 1836-1856. Thesis. Tulane University of Louisiana, 1970. New Orleans: Tulane U, 1970. Print. Amans notably painted portraits of Presidents Andrew Jackson and Zachary Taylor.

[21] Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. “The Octoroon: A Tragic Mulatto Enslaved by 1 Drop.” The Root. Donna Byrd, n.d. Web.

Consulted Works:

- Savage, Kirk. “Chapter 3: Imagining Emancipation.” Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-century America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1997. N. pag. Print.

- Boucicault, Dion. The Octoroon, Or, Life in Louisiana (1859). Brooklin, ME: Feedback Theatre & Prospero, 2002. Print.

- Hosmer, Hezekiah L. The Octoroon. New York: Follett, Foster, 1863. Print.

[22] McNeill, Tamara. “The Politics of Identity and Race in the Colored Creole Community: The Gens de Couleur Libre in Creole New Orleans, 1800–1860.” The McNair Journal. 2004.

[23] Edict of Good Government, July 2, 1784, Digest of the Acts and Deliberations of the Cabildo, Laws, Volume 1, Book 3, p. 105-112

[24] Prospect New Orleans – Home. Prospect New Orleans – Home. Firelei Báez’s work for P.3 explores the tignon

[25] Frazier, Nancy. “Portraits/Portraiture.” The Penguin Concise Dictionary of Art History. New York: Penguin Reference, 2000. Print.

[26] Frazier, Nancy. “Portraits/Portraiture.” The Penguin Concise Dictionary of Art History. New York: Penguin Reference, 2000. Print.

[27] Wallis, Brian. “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes.” American Art 9.2 (1995): Page 54. JSTOR. The University of Chicago Press on Behalf of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Web. 26 Feb. 2015. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109184>.

[28] Wallis, Brian. “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes.” American Art 9.2 (1995): 38-61. JSTOR. The University of Chicago Press on Behalf of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Web. 26 Feb. 2015. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109184>.

This is an excellent essay and discusses some very complex themes in a lucid and and concise manner. As a time period, antebellum New Orleans can be very difficult to discuss without oversimplification, of which this essay is not guilty. I like the way the argument unfolds. It is subtle and has the same kind of delicacy as Women in a Red Headdress. I was also impressed by the way in which the images themselves move the piece along, and recommended this essay to a student interested in the subject.

Well done, Rebecca! You’ve done a very good job of situation Amans’s Creole in a Red Headdress within both its historical and art historical contexts and have provided a clearly articulately, provocative thesis for the reader to consider. Moreover, in addition to strong visual analyses that provide your primary evidence, you’ve done an admirable job of supporting your ideas with primary and secondary literature. You should be proud of your essay and all the hard work it took to bring it to this point.